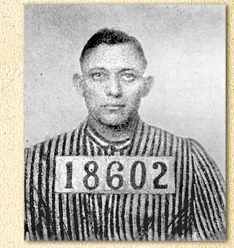

Otto Wood - North Carolina’s One-Man Crime Wave

by Marshall Wyatt

On Sunday morning, May 11, 1924, Raleigh’s News & Observer ran a front page headline that was sure to grab the attention of readers: “Two Convicts Make Daring Escape From State Prison.” The instigator of the escape plot was convicted murderer Otto Wood, incarcerated at North Carolina’s Central Prison in Raleigh for the killing of a Greensboro pawnbroker. His accomplice was John Starnes, serving a 5-year stretch for larceny. On Sunday morning, May 11, 1924, Raleigh’s News & Observer ran a front page headline that was sure to grab the attention of readers: “Two Convicts Make Daring Escape From State Prison.” The instigator of the escape plot was convicted murderer Otto Wood, incarcerated at North Carolina’s Central Prison in Raleigh for the killing of a Greensboro pawnbroker. His accomplice was John Starnes, serving a 5-year stretch for larceny.

At 6:00 a.m. on May 10th, the two men overpowered the supervisor of the prison’s chair factory, D. A. Partin, took his pistol, and forced him behind the wheel of an automobile owned by the prison physician. With his own weapon pressed against his ribs, Partin drove the two convicts through the prison gates to freedom. The escapees released their hostage at the Seaboard rail yard, then drove to New Bern Avenue where they ditched the physician’s car and hijacked a truck from Sanderford’s sausage factory. When this vehicle broke down on the outskirts of Durham, the two men commandeered a Studebaker car at gunpoint and headed for Winston Salem, where they picked up Wood’s wife and 5-year-old daughter. The foursome continued to Roanoke, Virginia, and here they were apprehended by police, who promptly returned Wood and Starnes to the penitentiary in Raleigh. Their taste of freedom had lasted all of 48 hours.

READ THE STORY

|

|

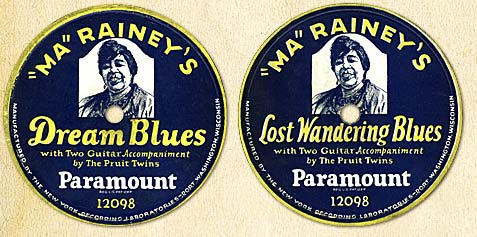

Paramount Portrait Labels

During its heyday of the 1920s, Paramount Records issued three discs with specially designed labels, each with a portrait of the recording artist. Two of these labels featured best-selling blues singers, while the third portrayed a lesser known preacher. Old Hat Records has acquired copies of the three discs, and presents the label graphics, front and back, with descriptions. During its heyday of the 1920s, Paramount Records issued three discs with specially designed labels, each with a portrait of the recording artist. Two of these labels featured best-selling blues singers, while the third portrayed a lesser known preacher. Old Hat Records has acquired copies of the three discs, and presents the label graphics, front and back, with descriptions.

READ THE STORY

|

|

Gastonia Textile Strike of 1929

by Patrick Huber

Patrick Huber is the author of Linthead Stomp, The Creation of Country Music in the Piedmont South

“Textile mill strikes flared up last week like fire in broom straw across the face of the industrial South,” Time magazine reported in an April 15, 1929 article titled “Southern Stirrings.” “Though their causes were not directly related, they were all symptomatic of larger stirrings in that rapidly developing region.” Between 1929 and 1931, an unprecedented series of textile strikes swept across the Piedmont South, fueled by declining wages and new managerial practices in the severely depressed industry. These strikes resulted in bitter standoffs between mill owners and mill workers, and significantly disrupted patterns of everyday industrial life in literally dozens of textile mill communities across the region. In 1929, eighty-one strikes involving more than 79,000 workers erupted in South Carolina alone. In a particularly appalling episode in October 1929, special sheriff’s deputies fired into a crowd of unarmed picketers at the Baldwin Mill in Marion, North Carolina, killing six and wounding twenty-five others. But the most famous strike that year occurred in Gastonia, North Carolina.

READ THE ESSAY |

Ella May Wiggins and The Mill Mother’s Song

by Patrick Huber

|

Ella May Wiggins' Tombstone

|

Patrick Huber is the author of Linthead Stomp, The Creation of Country Music in the Piedmont South

By far, the most famous balladeer to emerge out of the Gastonia Textile Strike of 1929 was Ella May Wiggins, a spinner at American Mill No. 1 in nearby Bessemer City and single mother of five whom the Communist press hailed as “the songstress of working class revolt in the South.” Only twenty-nine years old, she had given birth to nine children, but had lost four of them in quick succession to the combined effects of malnutrition and disease. Her ne’er-do-well husband deserted her and the children sometime in the mid-1920s, and thereafter Wiggins struggled single-handedly to raise her five surviving children, the oldest of whom was only eleven, on her weekly wages of $9. Margaret Larkin, who published two insightful 1929 articles on the Gastonia balladeer for The Nation and New Masses, attributed Wiggins’s union activism and her vision of social justice to her heartbreaking experiences as a single working mother. “I never made no more than nine dollars a week, and you can’t do for a family on such money,” Wiggins told crowds of fellow strikers in her speeches...That’s why I come out for the union, and why we all got to stand for the union, so’s we can do better for our children, and they won’t have lives like we got.”

READ THE ESSAY

|

|

Governor Al Smith For President

The Story of the Carolina Night Hawks

by Marshall Wyatt

|

Charles Miller and Family, Ashe County, North Carolina, circa 1928. Left to right: Ella Mae, Charles, Lillie, Hattie, Howard, Clifford (sitting). Charles and Howard were core members of the Carolina Night Hawks.

|

On April 17, 1928, four musicians from Ashe County, North Carolina, stood before a microphone in Atlanta, Georgia to voice their support for presidential hopeful Alfred E. Smith, four-term governor of the state of New York. Recruited by the Columbia Phonograph Company, the band arrived in Atlanta prepared with an original song promoting Smith’s bid for the Democratic nomination.

Al Smith was a Yankee, a Catholic, and a candidate who advocated the repeal of the 18th Amendment. Initiated in 1920, the 18th Amendment ushered in the age of Prohibition, America’s attempt to outlaw alcoholic beverages. Most Southerners supported Prohibition, even though illicit distilleries flourished in the region, often with tacit approval by law enforcement officials. This irony did not escape the notice of humorist Will Rogers, who quipped: “Southerners will continue to vote dry as long as they can stagger to the polls.”

READ THE STORY

|

“Every County Has Its Own Personality”

An Interview with County Records’ David Freeman

|

“I wanted a name that would imply ‘rural,’ the rural aspect of music fascinated me, as opposed to the city music I grew up with. Every county has its own personality, its own musical tradition. You can go from one place to another and pick up the subtle differences.”

|

David Freeman is a busy man. Over the years he has combined his love of music and a collector’s instinct with a keen business sense, carving his own distinctive niche in the recording industry. In 1964, while living in New York, he brought out his first LP anthology on the County label, beginning a string of reissues that showcased the great old-time string bands from the prewar era, records that drew heavily on Freeman’s own collection of 78s. County also began a series of live recordings by old-time musicians, including such luminaries as Kyle Creed and Tommy Jarrell. In 1965, Freeman quit his job with the railway post office and began selling country records as a full-time pursuit. In 1974, he left behind the bright lights of the big city and moved to Floyd, Virginia, population 400.

READ THE INTERVIEW

|

Violin, Sing The Blues For Me

African-American Fiddlers on Early Phonograph Records

by Marshall Wyatt

|

Many black musicians active during the 1920s and ’30s came from a string-band tradition rooted in the 19th century, an era predating the blues when fiddles and banjos were the predominant instruments.

|

When Lonnie Johnson exclaimed, “Violin, sing the blues for me!” during a recording session for Okeh Records in 1928, he was in top form, performing with passion and artistry on the instrument that was his first love—the fiddle. By the time Johnson recorded his Violin Blues, he was already one of the most prolific and influential musicians in the field of blues, an African-American musical form then dominated by guitar players, just as it is today. Johnson himself led a long and illustrious career as a guitarist, and is primarily remembered for his dazzling mastery of that instrument. But it was the violin that first captured his imagination, and his early career in New Orleans was spent honing his skills as a fiddler, first in his father’s string band, then as a young professional performing on excursion boats along the Mississippi.

READ THE ESSAY

|

|

|