Violin, Sing The Blues For Me Violin, Sing The Blues For Me

African-American Fiddlers on Early Phonograph Records

by Marshall Wyatt

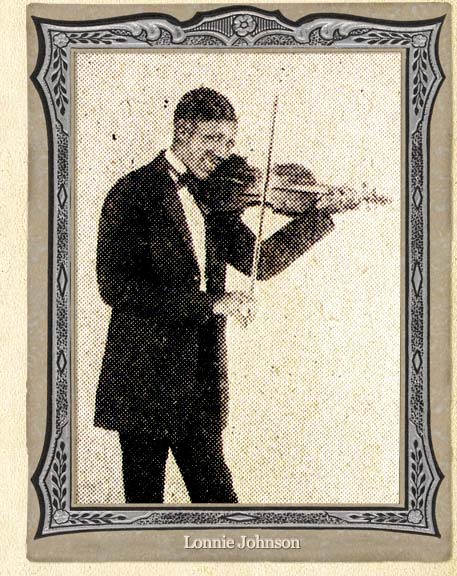

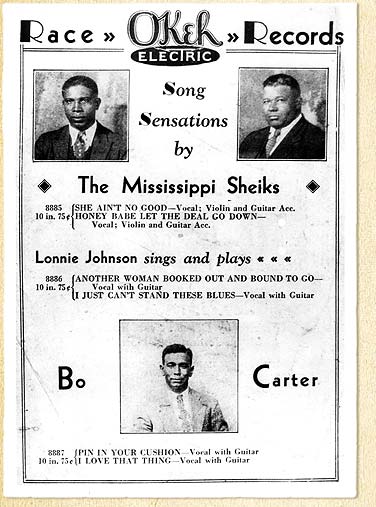

When Lonnie Johnson exclaimed, “Violin, sing the blues for me!” during a recording session for Okeh Records in 1928, he was in top form, performing with passion and artistry on the instrument that was his first love- the fiddle. By the time Johnson recorded his Violin Blues, he was already one of the most prolific and influential musicians in the field of blues, an African-American musical form then dominated by guitar players, just as it is today. Johnson himself led a long and illustrious career as a guitarist, and is primarily remembered for his dazzling mastery of that instrument. But it was the violin that first captured his imagination, and his early career in New Orleans was spent honing his skills as a fiddler, first in his father’s string band, then as a young professional performing on excursion boats along the Mississippi. Johnson signed with Okeh in 1925, and played violin on nearly two dozen early recordings. There’s no doubt that his fiddling played a significant role in the early history of recorded blues, even if it was soon eclipsed by guitar. The violin is by nature a lead instrument that can replicate vocal expressions through the use of vibrato and sliding notes, techniques that Johnson developed on the fiddle and later applied to guitar, creating the interplay of voice and instrument that is a prime ingredient of the blues.

Many black musicians active during the 1920s and ’30s came from a string-band tradition rooted in the 19th century, an era predating the blues when fiddles and banjos were the predominant instruments, and guitars a rarity. Although the blues signaled a major shift in African-American music, the older traditions proved resilient, and a number of black string bands were documented on early phonograph records in spite of marketing strategies that frequently excluded them. Record company executives, ever mindful of profit margins, were impressed with the sweeping popularity of blues music among black audiences, and felt reluctant to take a chance on the older forms of African-American music. Black fiddlers and string bands, still common in the South throughout the 1920s, were not entirely ignored by the record industry, but were they were sadly under-represented. Many black musicians active during the 1920s and ’30s came from a string-band tradition rooted in the 19th century, an era predating the blues when fiddles and banjos were the predominant instruments, and guitars a rarity. Although the blues signaled a major shift in African-American music, the older traditions proved resilient, and a number of black string bands were documented on early phonograph records in spite of marketing strategies that frequently excluded them. Record company executives, ever mindful of profit margins, were impressed with the sweeping popularity of blues music among black audiences, and felt reluctant to take a chance on the older forms of African-American music. Black fiddlers and string bands, still common in the South throughout the 1920s, were not entirely ignored by the record industry, but were they were sadly under-represented.

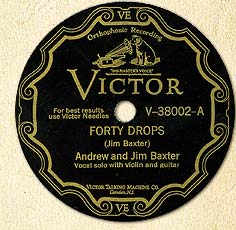

Some black string bands incorporated blues into their repertoires in order to keep abreast of trends. It was also common practice to rename material, calling it blues, even if it did not conform to the specific harmonic sequences and verse patterns of actual blues. Beginning in 1926, “Peg Leg” Howell performed a number of guitar blues for Columbia Records in Atlanta, but he also joined with his “Gang” to record rollicking stomps and rags, led by Eddie Anthony's wailing fiddle. The Afro-Cherokee fiddler Andrew Baxter, of Calhoun, Georgia, brought a graceful lyricism to his Victor recordings of 1927-29, and even waxed one tune with a white string band, The Georgia Yellow Hammers. Some black fiddlers, including Clifford Hayes and Will Batts, found a niche playing in the jug bands that flourished in Louisville and Memphis throughout the 1920s. When fiddler James Cole made records for Gennett in the early 1930s, he included minstrel songs, hillbilly tunes, and tin pan alley numbers. The Mississippi Sheiks, based in Jackson, found success with their blend of blues and country fiddle music, and scored a hit record for Okeh in 1930 with their original Sitting On Top of the World, which soon became a standard with black and white musicians alike. The fiddle-guitar duo known as the Alabama Sheiks fared less well- their two records for Victor were released in 1931, a time when industry sales were crippled by the Great Depression.

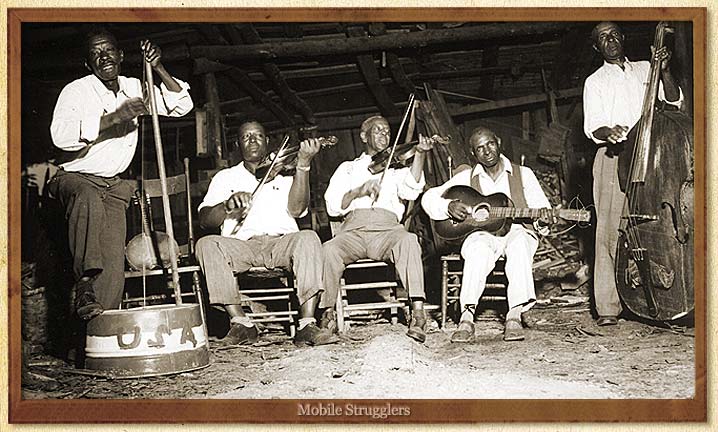

As the record business began to rally in the mid-1930s, musical trends became rapidly modernized due to the spreading influence of mass media, and black fiddlers found even fewer recording opportunities. In 1934, the Memphis Jug Band recorded jazzy, upbeat performances for Okeh that featured the fiddling of Charlie Pierce, but even their new sound was not enough to ensure continued popularity with the record buying public. These sessions would be their last. The following year, Big Bill Broonzy played fiddle on records by the State Street Boys, but these sides were anomalies in his long career as a blues guitarist. In the 1940s it was not the prominent commercial labels, but folklorists and aficionados who documented the older forms of African-American music, often using portable recording equipment. In 1942, John Work of Fisk University in Nashville captured the performances of a black square dance band comprised of fiddler Frank Patterson and banjoist Nathan Frazier, although the music remained unissued for more than forty years. In 1949, the Mobile Strugglers, a rustic black string band with twin fiddles, recorded for Bill Russell’s American Music label, but already they were an anachronism. By mid-century, black fiddlers on commercial records were virtually extinct. As the record business began to rally in the mid-1930s, musical trends became rapidly modernized due to the spreading influence of mass media, and black fiddlers found even fewer recording opportunities. In 1934, the Memphis Jug Band recorded jazzy, upbeat performances for Okeh that featured the fiddling of Charlie Pierce, but even their new sound was not enough to ensure continued popularity with the record buying public. These sessions would be their last. The following year, Big Bill Broonzy played fiddle on records by the State Street Boys, but these sides were anomalies in his long career as a blues guitarist. In the 1940s it was not the prominent commercial labels, but folklorists and aficionados who documented the older forms of African-American music, often using portable recording equipment. In 1942, John Work of Fisk University in Nashville captured the performances of a black square dance band comprised of fiddler Frank Patterson and banjoist Nathan Frazier, although the music remained unissued for more than forty years. In 1949, the Mobile Strugglers, a rustic black string band with twin fiddles, recorded for Bill Russell’s American Music label, but already they were an anachronism. By mid-century, black fiddlers on commercial records were virtually extinct.

Eventually, a few black fiddle players returned to the studio, most often for small specialist labels. Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown first recorded on fiddle in 1959 for the Peacock label in Houston. Other black fiddlers representing older styles emerged during the folk revival of the 1960s, including Butch Cage of Mississippi and Beaufort Clay of Tennessee, both of whom recorded for Arhoolie Records. Howard Armstrong renewed his career in the 1970s playing mandolin and fiddle with “Martin, Bogan & Armstrong” on albums for Rounder and Flying Fish. Armstrong was the subject of Terry Zwigoff’s 1985 documentary film, Louie Bluie, a portrait of an artist whose recording activities would span seven decades, beginning with his first Vocalion session in 1930. In a conversation with Zwigoff, Armstrong described his early love of the fiddle:

“And now, I was happy for a while, playing my old daddy’s potato-bug mandolin. But one day there was a blind man who came to town from Knoxville playing the fiddle, named Roland Martin. He’d show up at the coal mines on payday and play for the workers and pass the hat around. He could play those old country tunes like Turkey in the Straw, Sourwood Mountain, and Downfall of Paris and make classics out of ’em! When I heard that I didn’t want too much more to do with the mandolin. The fiddle, that was my instrument, I wanted to learn to play! And so, my dad didn’t have money to buy me a violin. So, he took a goods box and a pocket knife and carved me one. Cut me out a little fiddle. I wish I had it today. It was a very neat instrument and it had a nice tone. And I ran a nag a half a day to get the hair off the tail to make the bow. He made me the bow with one of my mother’s curtain sticks, you know. And so, I started whittlin’ away on the fiddle.”

African-American fiddlers on early phonograph records offer a rich variety of technique and material, yet many share stylistic traits that distinguish their music from that of white performers. Their approach is strongly rhythmic, with a penchant for improvisation that may stray from the melody. They use the violin to paraphrase the human voice, with flexible phrasing and shifting tones that echo the nuances of the singer. Spontaneity is valued over rote performance, and these fiddlers often engage in repartee with colleagues and listeners as they play. Such tendencies are evident on many early recordings, ranging from the rough Delta blues of Henry Sims to the polished jazz of Leroy Pickett. It should be noted, however, that some black fiddlers, such as Jim Booker of Kentucky, recorded hoe-down music much like that of their white contemporaries. So it would be a mistake to pigeonhole black and white fiddling styles, especially considering the long history of musical exchanges between the races.

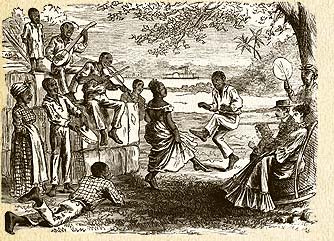

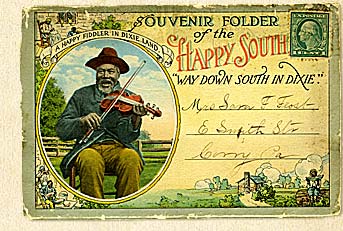

American vernacular music, especially in the South, has been shaped by this rich interplay of black and white over a period of three centuries, beginning when Africans were first exposed to European instruments aboard the slave ships that brought them to the New World. Slave fiddling in the American colonies was documented as early as the 1690s, and during the 18th century black fiddlers became as prevalent on Southern plantations as black banjo players. Over time, the traditions of Africa and Europe meshed in a complex chemistry to create uniquely American music. Together, the European violin and the African banjo would become the predominant folk instruments of the American South in the 19th century- a testament to the integration of two musical cultures. American vernacular music, especially in the South, has been shaped by this rich interplay of black and white over a period of three centuries, beginning when Africans were first exposed to European instruments aboard the slave ships that brought them to the New World. Slave fiddling in the American colonies was documented as early as the 1690s, and during the 18th century black fiddlers became as prevalent on Southern plantations as black banjo players. Over time, the traditions of Africa and Europe meshed in a complex chemistry to create uniquely American music. Together, the European violin and the African banjo would become the predominant folk instruments of the American South in the 19th century- a testament to the integration of two musical cultures.

In the antebellum South, slave fiddlers provided music at plantation balls and other entertainments for whites, and were often encouraged by their masters to play for the dancing of fellow slaves as well. Black musicians absorbed the polkas, marches, jigs and reels of the European tradition, but applied syncopated rhythms and minor tonalities derived from Africa. They were often granted privileges denied to field slaves, including a chance to travel when their services were required at other venues. Solomon Northup, a free man from New York who was kidnaped and sold into slavery in Louisiana, later described how his ordeal was mitigated by his ability to play the fiddle. In his book Twelve Years A Slave, published in 1853, Northup wrote:

“Alas! had it not been for my beloved violin, I scarcely can conceive how I could have endured the long years of bondage. It introduced me to great houses- relieved me of many days’ labor in the field- supplied me with conveniences for my cabin- with pipes and tobacco, and extra pairs of shoes, and oftentimes led me away from the presence of a hard master, to witness scenes of jollity and mirth. It was my companion- the friend of my bosom triumphing loudly when I was joyful, and uttering its soft, melodious consolations when I was sad. It heralded my name around the country- made me friends, who, otherwise would not have noticed me- gave me an honored seat at the yearly feasts, and secured the loudest and heartiest welcome of them all at the Christmas dance.”

Many slave fiddlers played European instruments, but others used homemade devices fashioned from gourds, much like the African banjo, only bowed instead of plucked. It is likely that some slaves imported from areas of West Africa took more readily to the European violin because of their experience with native instruments that resembled the fiddle, such as the goge. The goge, common throughout the savannah belt, consists of a calabash resonator covered with reptile skin and a single string made of horsehair, played with an arched bow. Fiddles made from gourds or even from sardine tins or cigar boxes, were current among blacks in America during slavery, and even into the 20th century. As late as 1935, the obscure “Dad” Tracy from Memphis recorded for the Bluebird label playing his homemade fiddle, performances that display the instrument’s remarkable versatility.

After Emancipation, some former slaves joined the ranks of professional musicians, performing in town squares, school houses or grange halls, as actual theaters were generally closed to black entertainers until well after the Civil War. Fiddles, banjos, and other stringed instruments were often favored, due in part to their low cost and easy mobility. Blacks and whites alike joined traveling medicine shows that combined music and comedy with patter designed to sell elixirs of dubious value. Black musicians who stayed closer to home could earn money playing at local square dances, or in barber shops and other gathering places, perhaps exchanging songs and tunes with white performers. Throughout the nineteenth century the violin remained the most common instrument among folk musicians of both races. After Emancipation, some former slaves joined the ranks of professional musicians, performing in town squares, school houses or grange halls, as actual theaters were generally closed to black entertainers until well after the Civil War. Fiddles, banjos, and other stringed instruments were often favored, due in part to their low cost and easy mobility. Blacks and whites alike joined traveling medicine shows that combined music and comedy with patter designed to sell elixirs of dubious value. Black musicians who stayed closer to home could earn money playing at local square dances, or in barber shops and other gathering places, perhaps exchanging songs and tunes with white performers. Throughout the nineteenth century the violin remained the most common instrument among folk musicians of both races.

Black music thrived in ports along the Mississippi, most notably New Orleans. By the 1840s, the Crescent City was known as a center for black fiddle music, and slaves from the region were often sent there to learn the instrument, returning to their home plantations as trained entertainers. Before the turn of the 20th century New Orleans witnessed the birth of jazz, a musical form that was largely defined by brass and reed instruments when it was first recorded in the early 1920s. However, a directory of Storyville musicians indicates that the earliest jazz bands in the city contained more violinists than trumpeters, banjoists, or saxophonists. And it was this rich musical climate of New Orleans at the turn of the century that shaped the talents of a young Lonnie Johnson as he first learned to fiddle.

We are fortunate that the fiddling of Johnson and others of his generation was captured on disc during the early decades of the 20th century. Their rare recordings demonstrate the depth and diversity of African-American fiddle music, not only in the popular blues music of the day, but also in the string band traditions that came before. For years, African-American fiddlers stood at the core of a complex musical evolution, in a time before folk traditions were skewed by the overriding demands of the marketplace. These old traditions may not thrive openly in today’s world, but they remain an indelible part of the fabric of American music. Those who listen to this music may be surprised to find a warmth and vitality that transcend the years, for these fiddlers speak very directly to the heart and soul. Their music is a steadfast conduit for human emotion, giving fresh life to Lonnie Johnson's old rallying cry, "Violin, sing the blues for me!"

|