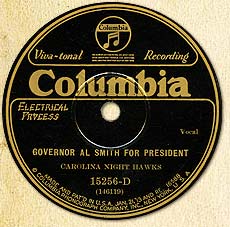

Governor Al Smith For President Governor Al Smith For President

The Story of the Carolina Night Hawks – by Marshall Wyatt

First published in The Old-Time Herald, Vol. 3, No. 6, November 1992.

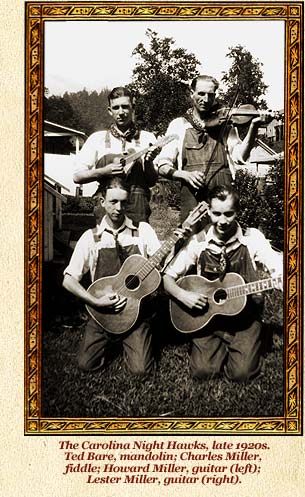

On April 17, 1928, four musicians from Ashe County, North Carolina, stood before a microphone in Atlanta, Georgia to voice their support for presidential hopeful Alfred E. Smith, four-term governor of the state of New York. Recruited by the Columbia Phonograph Company, the band arrived in Atlanta prepared with an original song promoting Smith’s bid for the Democratic nomination. The song, entitled simply Governor Al Smith For President, was penned by the group’s banjoist Donald Thompson, and sung in a high tenor by mandolinist Ted Bare. Providing the instrumental lead was 15-year-old Howard Miller on fiddle, backed on guitar by his father, Charles Miller. The tune was a familiar one, White House Blues, but the lyrics were all new:

Cal in the White House preparing

for his rest,

Al and his buddies are doing their best,

He’ll win, bound to win!

Hoover in the North land,

He’s firing his gun,

Smith’s in Dixie winning every one,

Hard to beat, hard to beat!

CLICK HERE TO SEE DONALD THOMPSON'S HANDWRITTEN LYRICS

CLICK ON A FORMAT TO HEAR “GOVERNOR AL SMITH FOR PRESIDENT”: WINDOWS MEDIA | QUICKTIME

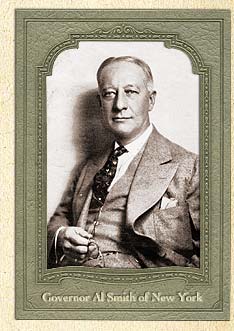

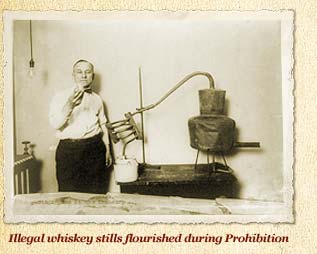

In 1927, Calvin Coolidge announced that he would not seek re-election, and Herbert Hoover became front runner for the Republican presidential nomination. Al Smith soon gained dominance in the Democratic arena, causing deep rifts among party stalwarts in the Southern states. Although the South traditionally backed Democratic candidates, many Southerners balked at supporting Smith- a Yankee, a Catholic, and a candidate who advocated the repeal of the 18th Amendment. Initiated in 1920, the 18th Amendment ushered in the age of Prohibition, America’s attempt to outlaw alcoholic beverages. The South was a stronghold of support for Prohibition, even though illicit distilleries flourished in the region, often with tacit approval by law enforcement officials. This irony did not escape the notice of humorist Will Rogers, who quipped: “Southerners will continue to vote dry as long as they can stagger to the polls.”

But not all Southerners fit this description, including Donald Thompson, a loyal Democrat and a staunch Smith supporter. Thompson realized that Prohibition only encouraged criminal activity and the unregulated production of spirits that often contained dangerous impurities:

We hear people shouting, no booze they say,

It’s running free now, you can get it any day

From bootleggers and killers too.

The sugar-head they make now will make you bounce around,

The brandy too will put you flat on the ground,

Bad stuff, hard to drink!

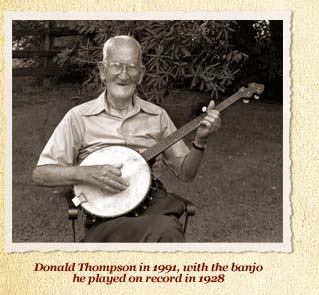

Thompson was born in Laurel Springs, North Carolina on June 10, 1901, and took an interest in music at an early age. He still remembers his first public performance: Thompson was born in Laurel Springs, North Carolina on June 10, 1901, and took an interest in music at an early age. He still remembers his first public performance:

My Daddy bought a banjo when I was seven years old, and I learned to pick. There was a boy down the road named Clay Reed. He was eight years old and he picked a banjo too. My Daddy and Mr. Reed scheduled a contest for me and Clay to pick against each other. We met at my aunt’s house, and there was a huge crowd gathered there. There must have been 200 people! And we both played and sang. And finally they called it a draw. They called it a draw because thery didn’t want to aggravate either one of us, you know.

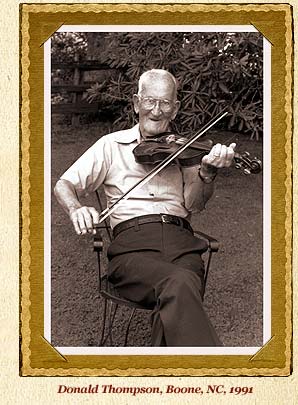

Later, Mr. Reed decided he wanted to buy a new violin for Clay, so my Daddy bought his old violin. It cost him two dollars. I started to play the violin when I was ten, and I was pretty good by the time I was twelve.

Soon the violin became young Donald’s instrument of choice, and his talents as a musician were in demand throughout the Laurel Springs community. He fiddled for square dances, parties, and school programs, often traveling on horseback to these events. Intent on acquiring a good education, Donald attended Jefferson Methodist Boarding School and later Jefferson High School, where he composed the school song for the class of 1922. Afterward, he began a long career as a school teacher, and continued his musical activities as well.

Ted Bare was a talented musician and singer, but his personality was in sharp contrast to Donald Thompson’s. Ted was well known for his rough and rowdy ways; he liked to ramble and he liked to drink. The son of a lawyer, Ted grew up near Big Ridge in Ashe County. As a young man he studied medicine for two years before dropping out of school to pursue the life of a musician. He was skilled on a variety of stringed instruments, including piano, but usually preferred playing the mandolin. In the mid-1920s, Ted began playing music with Charles and Howard Miller, an association that would last many years. Ted Bare was a talented musician and singer, but his personality was in sharp contrast to Donald Thompson’s. Ted was well known for his rough and rowdy ways; he liked to ramble and he liked to drink. The son of a lawyer, Ted grew up near Big Ridge in Ashe County. As a young man he studied medicine for two years before dropping out of school to pursue the life of a musician. He was skilled on a variety of stringed instruments, including piano, but usually preferred playing the mandolin. In the mid-1920s, Ted began playing music with Charles and Howard Miller, an association that would last many years.

Charles Miller, the senior member of the group, was born in 1887 along Stagg Creek near Comet, North Carolina. He learned to play fiddle from his father, Monroe Miller, who taught him a repertoire of traditional mountain tunes. At age 24, Charles married Hattie Barr of Horse Creek, and began raising a family. Their son Howard, born in 1912, began playing the fiddle when he was just a toddler. By the time Howard reached his teen years he was the premier fiddler of the Miller clan, and Charles soon switched to guitar.

In 1927, Ted Bare recruited Donald Thompson to join the band. Thompson gives the following account:

I first met Ted Bare in West Jefferson, and he said, “I play the mandolin, I hear you can pick a banjo. Would you like to be in our group?”And I said, “I might.”

So we got together with the Millers and started practicing. Now I was playing the fiddle all the time till I got with them, then I took the banjo. I bought a homemade banjo, paid $60 for it. That was the best sounding thing you ever heard. It was a dandy! Now Ted had a Gibson mandolin and I think Mr. Miller had a Gibson guitar. And Howard played the fiddle. For a youngster he could really play that thing!

We practiced at my home a week at a time, then we’d go to the Miller home and practice a week at a time. We played old country music, we didn’t know any other kind! After a while wedecided it was about time for the band to have a name. And Teddy came up with one, he called us the Carolina Night Hawks.

The Night Hawks built up a repertoire of more than 100 tunes. They played traditional fiddle pieces such as Cripple Creek, Sally Gooden, Arkansas Traveler, and Raggedy Ann. Old-time songs included Casey Jones, John Henry, and Old Joe Clark. The band performed waltzes such as Dewey Dewey Day and Over the Waves, and the occasional pop song like Carolina Moon. They also played Dixie, Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down, Going Down The Road Feeling Bad, and many more.

Soon the Carolina Night Hawks were performing all over Ashe and Alleghany Counties at private homes, school houses, box suppers, square dances, cake walks, and corn shuckings. Donald and Ted both owned Fords, but travel was not always easy. J.H. Brooks, a longtime friend of Howard Miller, recalls this story:

Howard told me one time that the band was heading to Laurel Springs to play at a box supper. They were driving an A-Model Ford, and they had a flat tire along the way, out there on somebody’s farm. They didn’t have a spare, so they took the tire off so they could patch up the tube. Howard and Ted started down to the creek off by the road there. He said they’d had a few drinks and were feeling pretty good. They figured they’d put the tube down in the water and watch for air bubbles so they could find the hole. They got down to the creek, and there were a bunch of cows that had waded out into the water. Ted thought he’d scare one of them, so he pitched the tube at it, and you know it went right around the cow’s neck! And they had to chase that old cow for two hours before they ever got their tube back! Howard told me one time that the band was heading to Laurel Springs to play at a box supper. They were driving an A-Model Ford, and they had a flat tire along the way, out there on somebody’s farm. They didn’t have a spare, so they took the tire off so they could patch up the tube. Howard and Ted started down to the creek off by the road there. He said they’d had a few drinks and were feeling pretty good. They figured they’d put the tube down in the water and watch for air bubbles so they could find the hole. They got down to the creek, and there were a bunch of cows that had waded out into the water. Ted thought he’d scare one of them, so he pitched the tube at it, and you know it went right around the cow’s neck! And they had to chase that old cow for two hours before they ever got their tube back!

Before long the Carolina Night Hawks would get a chance to travel in grander style. A local dealer in phonograph records, John Richardson, wrote the Columbia Phonograph Company to suggest an audition for the Night Hawks. A Columbia talent scout traveled to West Jefferson to hear the band, and agreed to send the foursome to Atlanta to make recordings. On April 16, 1928, the group left West Jefferson in a large Buick sedan rented by the phonograph company. Donald Thompson recalls the trip:

”We went in a Buick and they paid all expenses. The first day we went as far as Greenville [SC] and got a hotel. The hotel had a large porch across the front facing the street. After supper we went out on the porch and started playing. A big crowd came and gathered around. They were standing out in the street, they were just everywhere!

Next day we went on to Atlanta. We went right to the studio building. A fellow met us and took us to a room and said we could start practicing, so we did. Finally the guy came back and took us into the studio. There was a whole jug of whiskey sitting there, and he said, ‘Do you all want a nip?’ Well, Ted took a nip, but the rest of us didn’t. Ted took a little, but not enough to hurt him. Then Ted, Howard, and Mr. Miller got up close to the microphone and they put me about eight feet behind. That banjo was loud you know. Then they said, ‘Now you watch the light. When the light comes on, you start.’

So we watched, and when it came on we just started and went straight on through and never made an error. Lots of times nowadays they have a terrible time making records. Practicing, practicing, practicing! But we never had to repeat a single song."

The Carolina Night Hawks recorded four songs that day: Butcher’s Boy, Nobody To Love, A Stern Old Bachelor, and finally Governor Al Smith For President. Afterward, the band left the Columbia studio and headed home, never to return. According to Donald Thompson:

“We didn’t have a contract. We never signed a thing, they just sent us down there and we made a record. That’s unusual. But after we got back home they sent us checks, they paid us around $100 apiece and expenses and all that. We had to eat, you know. They paid that too. We had a good time!

And one thing, we weren’t scared when we went in there. I wasn’t a bit scared, and the rest weren’t either. Usually you get a little nervous. I wasn’t a bit nervous. Old Ted just went right into it. We didn’t know anything about recording, never seen a studio. When we finished recording, they played it back to us, and it sounded mighty good!"

Columbia released Governor Al Smith For President on June 10, 1928. It would be the only song ever issued by the Carolina Night Hawks. On the reverse side of the disc was a recording by Columbia’s most prolific country artist, Al Craver, better known as Vernon Dalhart. Dalhart’s selection was The Sidewalks of New York, Governor Al Smith’s official campaign song. Columbia, hoping to exploit Smith’s current wave of popularity, had the record in stores by the time Democrats convened in Houston, Texas, on June 26th. A majority of delegates to that convention agreed with Donald Thompson: Columbia released Governor Al Smith For President on June 10, 1928. It would be the only song ever issued by the Carolina Night Hawks. On the reverse side of the disc was a recording by Columbia’s most prolific country artist, Al Craver, better known as Vernon Dalhart. Dalhart’s selection was The Sidewalks of New York, Governor Al Smith’s official campaign song. Columbia, hoping to exploit Smith’s current wave of popularity, had the record in stores by the time Democrats convened in Houston, Texas, on June 26th. A majority of delegates to that convention agreed with Donald Thompson:

Let’s nominate Al Smith, nominate I say,

Then he’ll fly through on election day,

Get through all the way!

He made a good governor, you all will agree,

He’ll make a good president, as good as can be,

Yes he will, yes he will!

Smith, however, did not fly through on election day. The nation’s electorate voted overwhelmingly for Herbert Hoover in November. Smith failed to carry even his home state of New York. Five Southern states, including North Carolina, broke ranks with the Democrats and came down solidly for Hoover. Smith’s defeat sent his career into steady decline; never again would he hold the political spotlight as he did in 1928. Even journalist H.L. Mencken, a long-time Smith supporter, would remark: “Smith has ceased to be the wonder and glory of the East Side and becomes a minor figure of Park Avenue.”

The Night Hawks’ one record failed to bring them any national attention, but they remained popular in their home territory. After the trip to Atlanta, the band continued playing throughout Ashe County, including a performance on the steps of the County Court House in Jefferson that drew a large and enthusiastic audience. But Ted Bare’s boisterous behavior at this event, fueled by alcohol, prompted Donald Thompson to quit the band. Thompson was ready to move on anyway; soon he would leave Ashe County to attend Appalachian State Teacher’s College in Boone, North Carolina.

Ted Bare and the Millers continued as a trio, and soon embarked on a tour of West Virginia. J.H. Brooks later gave this account:

“Howard told me about going up to West Virginia to play music. One time they were playing on a street corner in Bluefield I believe he said. And they drew such a crowd that a policeman had to come and break it up. That policeman said he was sorry, he liked the music too, you know, but he couldn’t have people blocking the street that way.

Later, a preacher came up to them and said, ‘I’m holding a tent service down here in the bottom, and I want you to go down there and play tonight.’ And Howard’s Daddy, Charles, said, ‘We don’t play at places like that. We don’t know any religious songs.’

And the preacher said, ‘I don’t care what you play as long as you get a crowd in. I’ll give you five dollars apiece to play a while.’ Now five dollars was a lot of money in those days. So Ted Bare said, ‘We’ll go play!’

So they went and started making music, playing their usual tunes, and they drew a crowd. And after a while the preacher came around and slipped five dollars into each of their pockets.

Afterwards, Charles said, ‘We won’t do this again.’ Charles was pretty religious and he didn’t think it was right. But Ted Bare said, ‘Yes we will. Hell, for five dollars I’ll go in there and preach the sermon!’”

The brief heyday of the Carolina Night Hawks lasted less than two years. On November 21, 1929, Ted Bare made four solo recordings for Gennett Records in Richmond, Indiana, but these were never issued. He would continue to play with the Millers during the next decade, but only sporadically. Ted’s wanderlust took him on frequent excursions around the country as he eked out a living with his mandolin during the Depression years.

Charles and Howard Miller stayed closer to home, still playing music but relying on farming to make ends meet. The Millers performed several times at the annual White Top Folk Festival in southwest Virginia, still using the name Carolina Night Hawks. On August 12, 1933, they were part of a special musical program at White Top for the festival’s guest of honor, Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of newly-elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had defeated Herbert Hoover in 1932. Charles and Howard Miller stayed closer to home, still playing music but relying on farming to make ends meet. The Millers performed several times at the annual White Top Folk Festival in southwest Virginia, still using the name Carolina Night Hawks. On August 12, 1933, they were part of a special musical program at White Top for the festival’s guest of honor, Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of newly-elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had defeated Herbert Hoover in 1932.

Howard Miller continued to improve as a fiddler. Sometime around 1929 he met the now-legendary blind fiddler G.B. Grayson, whose music would profoundly influence him. Gilliam Banmon Grayson lived in Laurel Bloomery, Tennessee, and made frequent trips to Ashe County to visit relatives who lived not far from the Millers. Young Howard learned many tunes from Grayson, including I Saw A Man at Close of Day, Handsome Molly, Short Life of Trouble, and Train 45. An auto accident claimed the life of Grayson on August 16, 1930, but Howard Miller would keep the spirit of his music alive, performing Grayson’s tunes for years to come.

Howard and his father also played with many of the finest young musicians in the area, including guitarist Dolphus Black, banjoist Fred Miller, and fiddlers Alonzo Black, Elmer Elliott, and Frank Blevins. J.H. Brooks recalls another playing partner:

“There was another guy that used to play with them. His name was Howard Wyatt. He was a left-handed fiddler, lived over in Konnarock, Virginia. Charles told me when they’d go to a fiddler’s convention that he’d put his son Howard and Howard Wyatt up side by side and when they’d play their bows would cross up there, you know. He said they’d play Train 45, especially around Abingdon and places like that along the rail line, and they’d always win first prize!”

Brooks also remembers how father and son would occasionally perpetrate a late night prank as they returned home from a musical performance:

“Lots of times Charles and Howard would be coming in late at night, maybe two o’clock, three o’clock, four o’clock in the morning, crossing those ridges, walking, trying to get back home. When they’d get up close to somebody’s house, they’d take Howard’s fiddle bow and saw on the bass strings of the guitar. It made the most ghostly sound! It sounded really scary there late at night. They’d scare people to death! They’d have people telling boogie tales for a month!”

Howard Miller married Brucie Mae Shatley in 1934, and began learning carpentry as a means to support his family. He continued to play music well into the 1950s, when he turned his attention to instrument-making and became known for his finely crafted handmade fiddles, mandolins, and dulcimers. His father Charles also worked at carpentry and cabinet-making, but eventually put aside his guitar and quit playing music. Charles Miller died of heart disease in the hospital at Blowing Rock, North Carolina on May 9, 1976. Howard quit music for a number of years, but resumed fiddling in the 1980s at the urging of his son, Harold Dean Miller, who backed his father on guitar. Howard’s style and repertoire in the late 1980s was much the same as it had been 50 years earlier. On June 15, 1990, Howard Miller died of cancer at home in West Jefferson.

Ted Bare’s later life was more erratic than that of the Millers. After a decade of rambling, he served as a cook in the U.S. Army during World War II, receiving an early discharge because of his age. After the war, Ted invented a machine for making cinder blocks, but the invention never paid off and Ted soon turned to furniture making. In the late 1940s he traveled to South Carolina and toured briefly with Carl Story and His Rambling Mountaineers, playing guitar and singing. Later he returned home to engage in Ashe County’s perennial industry- making moonshine whiskey. This enterprise earned him sufficient funds to attend photography school in Baltimore for a year, before returning to West Jefferson where he operated his own photography studio throughout most of the 1950s. Ted often photographed touring musicians for the local newspaper, including such luminaries as Buddy Holly and Jerry Lee Lewis. In the mid-1960s he lived briefly West Palm Beach, Florida, where he once hosted an all-night jam session for British rockers Eric Burden and the Animals. Ted Bare’s checkered career ended in 1970 when he died of heart failure in Hudson, North Carolina, at age 67. Surviving are seven children from two of his three marriages. Ted Bare’s later life was more erratic than that of the Millers. After a decade of rambling, he served as a cook in the U.S. Army during World War II, receiving an early discharge because of his age. After the war, Ted invented a machine for making cinder blocks, but the invention never paid off and Ted soon turned to furniture making. In the late 1940s he traveled to South Carolina and toured briefly with Carl Story and His Rambling Mountaineers, playing guitar and singing. Later he returned home to engage in Ashe County’s perennial industry- making moonshine whiskey. This enterprise earned him sufficient funds to attend photography school in Baltimore for a year, before returning to West Jefferson where he operated his own photography studio throughout most of the 1950s. Ted often photographed touring musicians for the local newspaper, including such luminaries as Buddy Holly and Jerry Lee Lewis. In the mid-1960s he lived briefly West Palm Beach, Florida, where he once hosted an all-night jam session for British rockers Eric Burden and the Animals. Ted Bare’s checkered career ended in 1970 when he died of heart failure in Hudson, North Carolina, at age 67. Surviving are seven children from two of his three marriages.

And what of Donald Thompson? While attending Appalachian State Teacher’s College, he courted Ola Triplett and eloped with her in 1932. In college he was active in theater productions and on the baseball diamond, where he acquired the nickname “Tommy,” a name he still uses today. After graduating, he continued his career as a school teacher and principal, later earning a master’s degree in education from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

As a steadfast Democrat, Thompson was no doubt pleased when Franklin Roosevelt defeated incumbent Herbert Hoover in the 1932 presidential race. Like Al Smith before him, Roosevelt supported the repeal of Prohibition, and this time a thirsty electorate agreed. On December 5, 1933, the repeal of the 18th Amendment became official. Donald Thompson’s lyrics, premature in 1928, had finally come to pass:

It won’t be long now till she will be free,

Then they’ll make corn liquor as pure as can be,

Free from lye and sugar too!

When booze went out we didn’t think then

That we would have a chance to get her back again,

She’s coming back, back again!

By the mid-1930s, Donald “Tommy” Thompson had stopped playing music altogether, although he continued to write songs. Twenty-five years later, two old friends from Ashe County convinced him to dust off his fiddle and start playing again. By 1960 the trio was performing on a regular basis: Tommy Thompson on fiddle, Charlie Cox on guitar, and Edison Nuckolls on banjo. Their repertoire contained many of the same tunes that the Carolina Night Hawks had performed decades earlier.

The trio broke up eight years later, and once again Thompson laid down his fiddle. Today, Tommy lives with his wife in Boone, North Carolina where he keeps busy with neighborhood committees, gardening, quilt-making, and songwriting. Over the years Tommy has written dozens of songs, many of them topical. In 1930 he wrote A Family Murder in Carolina, describing the infamous Lawson family killings that occurred on Christmas day in 1929. During World War II, Tommy wrote I’ll Keep Fighting On, and during the 1960s he penned I’m a Prisoner of L.S.D. As recently as 1991 he wrote What the Yankee Doodle’ll Do, about the war in the Persian Gulf. Other original songs include I’m a Stranger, You Hit the Jack-Pot In My Heart, A Lonely Mountain Gal, and Will You Love Me When I’m Old?

Even today, Tommy Thompson is proud of Governor Al Smith For President, the song he wrote so many years ago and recorded with the Carolina Night Hawks.: Even today, Tommy Thompson is proud of Governor Al Smith For President, the song he wrote so many years ago and recorded with the Carolina Night Hawks.:

“I was a Democrat then, I’m still a Democrat now! Dyed in the wool! I was hoping our record would help Al Smith, but I don’t think it ever got far enough along to help him much. He got defeated. Even so, I think we did a pretty good job on our record. I hate now that we didn’t stay together. We could have gone on to Nashville! Back then music wasn’t such a big business like today. Boy, can they play now, brother! Those guitarists today, they can carry on! But this old-time music is hard to beat, you know it? Old mountain music, that’s hard to beat!”

Sincere thanks go to the following persons for supplying information needed to compile this history: Donald Thompson, Howard Miller, Brucie Miller, Harold Dean Miller, Bruce Miller, J.H. Brooks, Arlene Brown, Monetta Ballard, Gary Bare, Ronald Bare, Grant Bare, Joyce Meyers, Craig Ventresco, Tom Hargrove, Frank Blevins, and Fred Miller.

Donald “Tommy” Thompson died on March 9, 1999 in Boone, North Carolina, in his 98th year. |