Gastonia Textile Strike of 1929

by Patrick Huber

Patrick Huber is the author of Linthead Stomp, The Creation of Country Music in the Piedmont South Patrick Huber is the author of Linthead Stomp, The Creation of Country Music in the Piedmont South

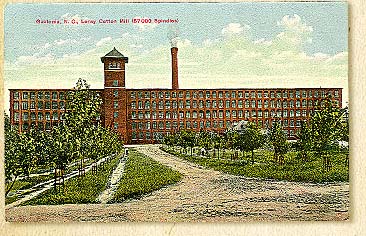

“Textile mill strikes flared up last week like fire in broom straw across the face of the industrial South,” Time magazine reported in an April 15, 1929 article titled “Southern Stirrings.” “Though their causes were not directly related, they were all symptomatic of larger stirrings in that rapidly developing region.” Between 1929 and 1931, an unprecedented series of textile strikes swept across the Piedmont South, fueled by declining wages and new managerial practices in the severely depressed industry. These strikes resulted in bitter standoffs between mill owners and mill workers, and significantly disrupted patterns of everyday industrial life in literally dozens of textile mill communities across the region. In 1929, eighty-one strikes involving more than 79,000 workers erupted in South Carolina alone. In a particularly appalling episode in October 1929, special sheriff’s deputies fired into a crowd of unarmed picketers at the Baldwin Mill in Marion, North Carolina, killing six and wounding twenty-five others. But the most famous strike that year occurred in Gastonia, North Carolina. There, the strike originated at the Loray Mill, a massive six-story brick factory that manufactured combed yarn and automobile tire cord fabric. With 2,200 workers and 132,000 spindles, the mill, a subsidiary of the Manville-Jenckes Company of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, was the largest textile plant in Gaston County, and had been the first in the county to introduce the notorious “stretch-out” system, the name millhands used to describe the industry-wide managerial practice of implementing labor-saving machinery and redistributing workloads. The stretch-out dramatically increased the amount of work required of spinners and weavers, at the same time often reducing their wages. In 1927, under these new cost-cutting measures, the Loray Mill superintendent laid off one-third of the plant’s 3,500 employees and trimmed a half-million dollars from the annual payroll without sacrificing production. After the layoffs, those millhands who still had jobs scrambled even harder to make a living under the nerve-wracking pressures of sped-up work rhythms and thinner pay envelopes. The Gastonia strike began on April 1, 1929, when 1,800 Loray Mill workers walked off their jobs to protest the intolerable shopfloor conditions under the stretch-out. Under the local leadership of Fred E. Beal, a thirty-three-year-old Massachusetts Communist who had secretly been organizing a union local in the plant since January, the National Textile Workers Union promptly called a strike. Among other concessions, the strikers demanded a minimum $20 weekly wage, a forty-hour work week, union recognition, and an end to the hated stretch-out. Within a few weeks, hundreds of workers from nearby Bessemer City and Pineville mills joined the rebellion.

Two days after the strike began, Governor O. Max Gardner, himself the owner of a nearby Cleveland County textile mill, sent five companies of National Guardsmen to the city to protect mill property and to maintain order on the picket line. The pro-business city newspaper, the Gastonia Daily Gazette, exacerbated already-heightened tensions in the community by publishing a series of inflammatory anti-Communist editorials accusing the NTWU organizers of advocating bloodshed and violence, race mixing, free love, the overthrow of the U.S. government, and the destruction of all things southerners held sacred. When the governor withdrew some of the state troops, mill owners and civic leaders organized a vigilante group called the “Committee of One Hundred” to patrol the strike zone. Shortly after midnight on April 18, using sledgehammers and crowbars, the Committee’s mob completely demolished the flimsy frame structures of the NTWU’s headquarters and relief store. Three weeks later, the Loray Mill evicted striking workers and their families from company-owned houses. By the end of April, most of the strikers in Gastonia had returned to the mills, with only some three-hundred steadfast strikers remaining on the picket lines and attending the mass meetings. Two days after the strike began, Governor O. Max Gardner, himself the owner of a nearby Cleveland County textile mill, sent five companies of National Guardsmen to the city to protect mill property and to maintain order on the picket line. The pro-business city newspaper, the Gastonia Daily Gazette, exacerbated already-heightened tensions in the community by publishing a series of inflammatory anti-Communist editorials accusing the NTWU organizers of advocating bloodshed and violence, race mixing, free love, the overthrow of the U.S. government, and the destruction of all things southerners held sacred. When the governor withdrew some of the state troops, mill owners and civic leaders organized a vigilante group called the “Committee of One Hundred” to patrol the strike zone. Shortly after midnight on April 18, using sledgehammers and crowbars, the Committee’s mob completely demolished the flimsy frame structures of the NTWU’s headquarters and relief store. Three weeks later, the Loray Mill evicted striking workers and their families from company-owned houses. By the end of April, most of the strikers in Gastonia had returned to the mills, with only some three-hundred steadfast strikers remaining on the picket lines and attending the mass meetings.

Over the next few months, however, the violence escalated. On the night of June 7, Gastonia police chief Orville F. Aderholt and several of his officers, at least two of whom were drunk, raided the union’s newly rebuilt headquarters and a tent colony set up to shelter the evicted strikers and their families. When armed union guards demanded to see a search warrant, one of the police officers snarled, “We don’t need any god-damned warrant.” Then, as another policeman scuffled with a union guard, shots rang out. A running gun battle ensued, and when the gunfire ceased, the police chief, three of his officers, and one union guard lay wounded. Chief Aderholt died the next morning. More than seventy organizers and strikers were arrested, and eventually sixteen of them, including Fred E. Beal and Vera Buch, the NTWU’s deputy strike leader, were indicted for conspiracy to murder, and put on trial, through a change of venue, in nearby Charlotte.

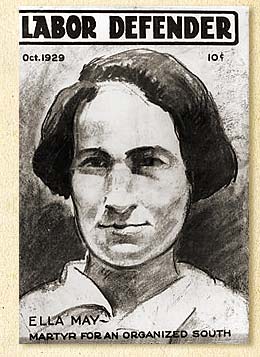

Throughout the remainder of the five-and-half-month strike, night-riding bands of hired mill thugs continued to terrorize union leaders and the three-hundred or so hold-out strikers. On September 9, after the first trial ended in a mistrial when a juror went insane, a mob stormed the rebuilt union headquarters and tent colony, kidnapped three NTWU organizers, and harassed strikers and their families. Five days later, in broad daylight, a caravan of gun thugs ambushed a truckload of unarmed Bessemer City strikers en route to a union rally in South Gastonia, and shot and killed Ella May Wiggins, a single mother of five and the strike’s most prolific balladeer. “Lord-a-mercy,” sensationalized newspaper articles claimed she gasped as she slumped against two strikers standing beside her, “they done shot and killed me.” Shortly after Wiggins’s murder, the Gastonia strike collapsed. The following month, October 1929, at a second trial in Charlotte, Fred Beal and six other defendants were convicted of conspiracy to murder in the death of Chief Aderholt and sentenced to prison terms ranging from five to twenty years. While awaiting their appeal to the North Carolina Supreme Court, all seven of the convicted men jumped bail and fled to the Soviet Union. Throughout the remainder of the five-and-half-month strike, night-riding bands of hired mill thugs continued to terrorize union leaders and the three-hundred or so hold-out strikers. On September 9, after the first trial ended in a mistrial when a juror went insane, a mob stormed the rebuilt union headquarters and tent colony, kidnapped three NTWU organizers, and harassed strikers and their families. Five days later, in broad daylight, a caravan of gun thugs ambushed a truckload of unarmed Bessemer City strikers en route to a union rally in South Gastonia, and shot and killed Ella May Wiggins, a single mother of five and the strike’s most prolific balladeer. “Lord-a-mercy,” sensationalized newspaper articles claimed she gasped as she slumped against two strikers standing beside her, “they done shot and killed me.” Shortly after Wiggins’s murder, the Gastonia strike collapsed. The following month, October 1929, at a second trial in Charlotte, Fred Beal and six other defendants were convicted of conspiracy to murder in the death of Chief Aderholt and sentenced to prison terms ranging from five to twenty years. While awaiting their appeal to the North Carolina Supreme Court, all seven of the convicted men jumped bail and fled to the Soviet Union.

In the following decades, the Gastonia Textile Strike of 1929 would achieve infamy as one of the bitterest labor struggles in the history of the union-busting South, an episode of industrial strife whose outbursts of anti-labor violence, deep social divisions, and intense red-baiting prompted a New York Times reporter at the time to describe it as nothing short of a “class war.” Despite the fact that the Gastonia Textile Strike of 1929 ranks as the defining moment in the twentieth-century history of Gaston County, the memory of the strike has been consigned to the historical shadows there and repressed for more than seven decades. “For more than fifty years, Gastonians developed collective amnesia about the single most important event in the community’s history,” writes historian John A. Salmond in Gastonia 1929: The Story of the Loray Mill Strike (1995). Despite this pervasive denial of history, dreadful memories of the strike continue to haunt Gastonia. “Even today,” notes Salmond, “the town of Gastonia is deeply divided over what to do with the now-abandoned Loray Mill. For some it is a symbol of a violent past best forgotten; for others it is the site of the most significant event in the town’s history and should therefore be preserved.”

|