First published in Wax Poetics, Issue #9, Summer 2004. Following are selected excerpts, beginning with Joe Allen's introduction:

As I was researching 78 collector Joe Bussard, it quickly became apparent that Marshall Wyatt’s story needed to be told as well. Marshall’s label Old Hat Records not only provided the access to the jewels of Bussard’s record collection with Down in the Basement (Old Hat CD-1004), but the impeccable 72-page accompanying booklet was clearly an invitation to further explore the world of 78s and the people who rescued them from oblivion. The other CDs in Old Hat’s catalog to date are equally important cultural documents of our American past, thoroughly researched and annotated, and beautifully presented complete with period photos, postcards, painting, drawing, and of course, record labels and sleeves. The booklets place the music in its historical, cultural, and social context and thereby significantly inform and direct the listener’s experience.

In addition to Old Hat Records, Marshall Wyatt has been publishing an ongoing series of interviews in The Old-Time Herald where he interviews notable 78 collectors. It is not surprising that when I turned the tables on Marshall, he provided a definitive blueprint for the cultural significance of the record collector and the raison d’etre for an independent reissue label.

Joe Allen: How do you view the role of the 78 record collector?

Marshall Wyatt: Record collectors no doubt have personal and private motivations, but they also take on roles that serve a much broader public. Among the 78 collectors I know are musicians, librarians, folklorists, radio hosts, historians, writers, editors, teachers, discographers, sound engineers, producers, record dealers, artists, filmmakers- the list goes on and on. And all of these people are involved in the world of 78 records and the body of music that 78s represent. Folk artists and folk musicians are sometimes described as “culture bearers,” and I think that collectors, in their various roles, are also deserving of that title. Collectors are preserving a cultural treasure for future generations.

The 78s I know best are commercially issued American records from the 1920s and ’30s, mostly from the South, so that’s my frame of reference. These records provide a lot of pure entertainment, and that in itself is important. They’re full of beauty and genius, and they say a lot about American culture. In the 1920s the music was heartfelt, and often very raw and quirky and personal. But recorded music changed profoundly in the 1930s, the recording industry changed and technology changed. The music became more formulaic and self conscious, and suddenly the older music was considered hopelessly dated, it was cast off and not appreciated. Fortunately, a small community of record collectors emerged, and they were the ones who saved this music from oblivion.

I think 78 collectors, like all collectors, are driven by deep seated forces. I’m sure a psychologist could lay out various explanations: “pivotal childhood events create obsessive-compulsive tendencies,” that kind of thing. Or maybe there’s some ancient biological need that comes into play. In my case, I had a positive example set by my father. He was a writer, historian, artist, and a lifelong collector. He had his day job, but he really loved those other pursuits- he was an amateur in the best sense of the word. I think 78 collectors, like all collectors, are driven by deep seated forces. I’m sure a psychologist could lay out various explanations: “pivotal childhood events create obsessive-compulsive tendencies,” that kind of thing. Or maybe there’s some ancient biological need that comes into play. In my case, I had a positive example set by my father. He was a writer, historian, artist, and a lifelong collector. He had his day job, but he really loved those other pursuits- he was an amateur in the best sense of the word.

JA: What led you to begin your series of interviews with 78 record collectors for the Old-Time Herald? Are there others besides Joe Bussard, David Freeman, Terry Zwigoff, and Bob Pinson?

MW: Those are the four, so far. And of course those four guys have things in common, but what’s interesting is how different their personalities are. Freeman is thoughtful and reserved, whereas Bussard is a real wildman. And the two of them traveled through the South hunting records together back in the ’60s. I’m sad to say that Bob Pinson died this past September [2003]. Bob was really soft spoken and modest, in spite of his considerable accomplishments. He spent 30 years building an amazing collection of records for the Country Music Foundation in Nashville.

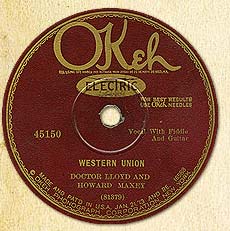

It was Terry Zwigoff who motivated me to start doing those interviews in the first place. I got to know him when I lived in California. I felt that our musical tastes had a lot in common, but he’d been a serious collector far longer than I had. Often I’d go over to Terry's house and he’d be excited about some record he’d just found: “Oh man, you gotta hear this! This is the greatest!” Then he’d put on something like Western Union by Doctor Lloyd and Howard Maxey, a completely off-the-wall hillbilly record from 1927, something I’d never heard before. So he expanded my horizons that way.

JA: How extensive is your own record collection?

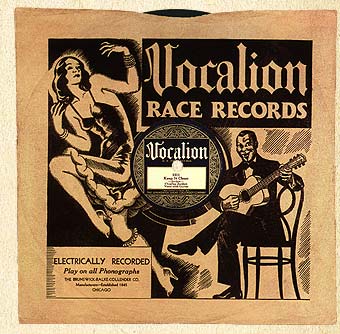

MW: It’s modest. The 78 collection seems to get less extensive all the time. By that I mean that I’m editing the collection, honing it down and getting rid of records that are not that interesting or where the condition doesn't measure up. I’ve probably got about 1,500 78s. That roughly breaks down into 350 race records, 1,000 hillbilly records, and 150 miscellaneous.

I also have a whole shelf of LPs, about 1,000 of them, and nearly all of them reissue music from the 78 era. The LPs make an excellent reference library- not only for the music, but also the liner notes, which often contain information available nowhere else.

The only CDs I collect systematically are those on the Yazoo and County labels, but I do have a good sampling from many other labels. Again, these are mostly reissue labels. I think this is a golden age for reissues- I'm sure there's more old music available now than ever before. I’ll admit I don’t follow the current music scene very closely.

JA: What is your most prized 78?

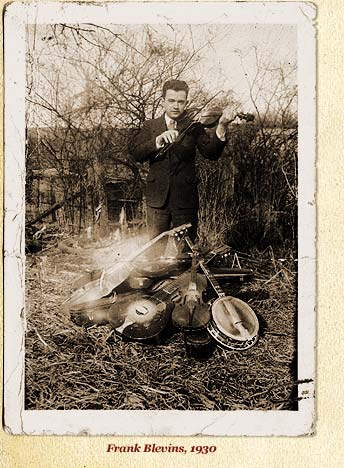

MW: My most prized 78 is Columbia 15765-D by Frank Blevins And His Tar Heel Rattlers. It came out in 1932, not many were pressed and not many have survived- there are just five or six copies of this record known within the collecting community. I actually have a couple of records that are more rare, but the Blevins record has such deep meaning for me because of my personal friendship with Frank Blevins. And of course both sides are absolute masterpieces.

JA: Do you have any of those Joe-Bussard-like record collecting stories? JA: Do you have any of those Joe-Bussard-like record collecting stories?

MW: I got in the game relatively late, so I don’t have a repertoire of fabulous stories like Joe does. But I will tell one:

I’ve hunted records at the Raleigh Flea Market over a period of years, and occasionally a decent record will turn up, like the Alabama Rascals on Perfect or Wilmer Watts on Broadway, that sort of thing. But when I moved back here from California in 1993, I found that I had a serious rival. Another record collector, who lived north of town, had made the Raleigh Flea Market his personal mission. He was there every week without fail and he knew all the dealers. And he was advanced as a collector, he knew the good stuff, and he was looking for many of the same records I was.

The Raleigh Flea Market generally doesn’t get started too early, so I was used to arriving around 9:00 am. But this other collector would already be there and he’d already be picking through records. So the next week I got there at 8:30, only to find that he’d arrived at 8:00. So the next week I got there at 7:30, but he’d figured out what I was up to, so he’d shown up at 7:00. It was getting ridiculous. What was I going to do, pitch a tent the night before?

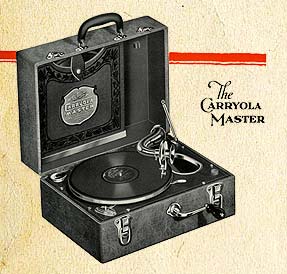

I realized I couldn’t get there earlier than this other guy, but I tried to be diligent once I did get there. One Saturday I showed up really late, about noon, so my expectations were not high. Then I spotted one dealer who was set up under a tree on the periphery of the flea market, and he had a lot of broken down furniture, really a pile of junk. There were no boxes of records, but I did notice what looked like a little suitcase back behind the tree. And it was all dusty and beat up, but I realized it was actually a portable Victrola. And of course I knew that these little phonographs always had a pocket built into the lid that would hold eight or ten records. So I opened the lid, and sure enough I found eight or ten records in that pocket. They were all gospel records, and not too interesting- until I got to the very last one. That’s when my heart skipped a beat. It was Paramount 12799, Prayer of Death, Parts 1 & 2 by Elder J. J. Hadley- a name that blues fans will recognize as a pseudonym for Charley Patton.

It’s a very interesting record. It sounds like he might have composed it spontaneously in the studio, which was unusual for Patton. It’s a rambling spiritual, a pastiche of several old religious songs combined with “talking” guitar. And that’s the only Charley Patton record I’ve ever found. It cost me a dollar. It’s a very interesting record. It sounds like he might have composed it spontaneously in the studio, which was unusual for Patton. It’s a rambling spiritual, a pastiche of several old religious songs combined with “talking” guitar. And that’s the only Charley Patton record I’ve ever found. It cost me a dollar.

JA: What led you to begin Old Hat Records?

MW: In a roundabout way, it was Frank Blevins. He was a fiddler who recorded a handful of sides for Columbia back in 1927 and ’28. When I lived in California in the 1980s, I'd go to a 78 swap meet every month up in El Cerrito, in the parking lot of Down Home Music. At one of those meets I found a record by “Frank Blevins And His Tar Heel Rattlers.” And that record had a profound effect on me, something about that music struck a deep emotional chord.

Later I found out that Frank Blevins was still living, and I tracked him down and went to visit him. That sparked a long running research project about Blevins and his colleagues who were active back in the ’20s and ’30s. I gathered a lot of information and I collected all of the 78s by musicians from Blevins’ home turf- Ashe County, North Carolina and Smyth County, Virginia. This was a superb body of music that had never been reissued on CD, and most of it had never been reissued in any form. So it seemed like a logical thing to do, to make a CD, to present the music in a thoughtful way. And by this time I’d spent years interviewing people and collecting old photographs, so I already had the information and the visuals to go with the music. That became the first album, Music From The Lost Provinces.

JA: How did you collect all of the 78s by musicians from Blevins' home turf ? How long did it take? How did you know which records you were looking for? JA: How did you collect all of the 78s by musicians from Blevins' home turf ? How long did it take? How did you know which records you were looking for?

MW: It's actually a fairly small group of records. I found out about them by talking to other collectors and by reading various articles and interviews. An interview with Ephraim Woodie had been published in Old Time Music magazine, and a short interview with Frank Blevins had appeared in The Devil's Box. Then I got to know Frank and several of his colleagues, and they filled in the gaps. It took me about six years to find clean copies of all of them. Some are common, but there were three that were tough to find, and that's why it took as long as it did. At first I ran a “wanted” ad in Joslin's Jazz Journal, and I found several records that way, a couple of real beauties in fact. Other records I got by bidding on auction lists, a couple I bought off of collectors I knew, and I traded for one of the rare ones. And I turned up a few of the records from people right there in Ashe County.

JA: How much time, effort, and research goes into one of your CD anthologies?

MW: I probably spend more time and effort than any rational person would devote to a project. It takes me a couple of years to produce one of these CDs, and it usually starts with an idea that’s been knocking around inside my head for a lot longer than that. I want to accelerate that process if I can, but I’m not going to compromise quality. Right now I’m working on three CDs simultaneously, which should yield results more quickly than working in a purely linear fashion.

Producing one of these CDs is a multifaceted process, and I’m involved every step of the way. I could describe those steps in detail, but I’m sure that would get tedious. Suffice it to say, I gather as much material as I can that pertains to the subject. The challenge then is to distill all of that information into a concise, coherent entity. I want to put the music into a proper historical context, but I’m not interested in a dry, academic exercise. I want the CD to be entertaining and engaging from start to finish. That’s what I try to do.

JA: Why do you include such extensive and varied accompanying booklets with each release?

MW: Why settle for a simple insert or foldout? Historical information and visual material can only enhance the music. It’s all important, and it all works together. I want to create a memorable package, something that has an impact. I want to make it as potent as possible, to make every detail count.

JA: Why do you include many photos of records sleeves and labels?

MW: This mainly applies to Down In The Basement, and there’s an obvious reason for that. The music on that album is derived from a particular record collection, and the booklet is devoted to record collecting. If you don’t know the world of 78 records, that album will give you a taste. And part of that world is the cult of the object. The music may be paramount, but to a collector that original piece of shellac is a crucial part of the equation. The labels, the sleeves, the ephemera, it's all part of the milieu, and I wanted to capture the flavor of that in the booklet.

JA: What role do the various images fulfill?

MW: The music doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Visual images help flesh out the world that produced the music. The images are important as historical documents, and they’re aesthetically appealing. To me, music and visual art are natural complements. I’m fascinated by old graphics and photographs. There’s a whole world of photographic imagery still waiting to be discovered- in closets and scrapbooks, or maybe under somebody’s bed in a shoe box. And there’s still a lot of material in archives and museums that hasn’t been thoroughly cataloged, just waiting for a researcher to dig it out.

JA: How do you go about locating and collecting such material? JA: How do you go about locating and collecting such material?

MW: I contact other collectors and researchers to see what they might have, and usually folks are happy to help out. And of course I’ll reciprocate if they ever need to borrow something of mine. Librarians at various museums and universities are often very helpful, although occasionally there's a lot of paperwork involved. It’s always great to find a picture that's never been published, or perhaps only published once in some obscure journal.

I read and collect books on whatever subject I’m involved with at the time, and I’m careful to study the bibliographies because that will lead you to other sources, sometimes very obscure ones. There are some great 19th century periodicals like Harper’s and Century that contain a wealth of beautiful drawings and graphics that relate to historical subjects.

The internet’s been a big help. A Google search can turn up all kinds of sources you never knew existed if you have the patience to sort through them. And Ebay has had a tremendous effect on collecting; it's flushed out countless items from every nook and cranny. It can also be addictive and expensive.

Most collectors that I know personally are very helpful in loaning materials for a project. If they trust you and respect the project you’re working on, then they’re happy to help out, and most of them do it for nothing: “Just send a copy of the CD when it's finished.” It’s heartwarming to know there are still folks like that, and I really couldn’t produce these CDs without them.

JA: To what extent is such exhaustive research and work on your part a money making enterprise for your record label?

MW: Nobody’s ever going to get rich off this kind of music. It’s been a struggle just to break even. But rather than cut corners to save money in the short run, I think it’s worth investing more to produce a quality product, because that’s what will bring sustained sales, which over time will create profit. I do anticipate increased revenues in the future, enough to keep this enterprise going.

JA: Do you consider the original 78 recordings in the Public Domain? Why or why not?

MW: I’m sure that some 78s are still under copyright, but the records I’m using are in the Public Domain. You’re not going to see artists on my albums who are big names or cash cows. I use recordings that were made in the late ’20s and early ’30s, and subject to the 28-year renewal rule. They came up for renewal in the 1950s. Most of these records had generated very little money when they were current, and by the ’50s they were almost completely forgotten. In addition, much of the music on these records comes from the folk tradition and was never under copyright to begin with.

JA: To what extent are you preserving the past?

MW: Record labels that reissue old 78s are transferring the music to a technology that’s current and accessible to modern audiences, so it keeps the old music alive. The past should be accessible, it’s a healthy thing. The appreciation of the past can enrich the present, and it can inspire future creativity. With 78 records, there’s something magical at work. A hundred years after a record is made, you can drop a stylus into the groove and hear those same sounds again. The record collector is like a medium who summons the dead.

JA: How should the original recording artists be rewarded for their artistic creation, now roughly 75 years out of circulation, and at the same time, how should their work be disseminated?

MW: Artists should certainly be compensated for their work, I’m all in favor of that. But for how long? The artists on the Old Hat CDs are now all dead, and their music is out of copyright, so perhaps that question is moot. But what about the families of the artists? In a perfect world, there’d be plenty of money to spread around, but when you’re dealing with obscure music of long ago, that’s never going to happen. At what point does the music or art simply belong to the ages? Should all the descendants of Shakespeare be getting a royalty check every month? It wouldn’t be practical, and it just doesn’t make sense. That’s why copyright time limits were established in the first place.

In the end, you can’t define everything in terms of dollars and cents. The lasting reward for everyone involved is the perpetuation of the music or the writing or whatever the art form happens to be, assuming the work has merit to begin with. And the small independent labels are the ones who do the most to disseminate the vernacular music of the prewar era- blues and hillbilly, early jazz and ethnic music, America's bedrock music.

Joe Allen is a professor of English in Poughkeepsie, NY,

whose research centers on cultural studies, popular music, and copyright law.

He is a regular contributor to Wax Poetics.

|