GASTONIA GALLOP

Cotton Mill Songs & Hillbilly Blues

Piedmont Textile Workers on Record

Gaston County, North Carolina 1927 - 1931

Artist Biographies

by Patrick Huber

Patrick Huber is the author of Linthead Stomp, The Creation of Country Music in the Piedmont South

DAVID McCARN DAVID McCARN

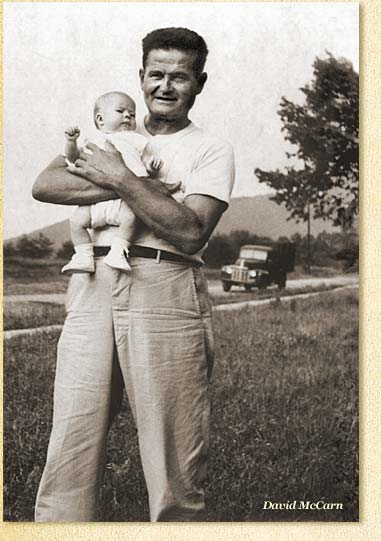

Although he made only a dozen commercial recordings between 1930 and 1931, one of the most critically acclaimed hillbilly recording artists to emerge out of Gaston County’s vibrant music scene was David McCarn (1905-1964). A native of Gaston County, born in the textile town of McAdenville in 1905, McCarn was the son of mill-worker parents. In 1917, at the age of twelve, McCarn began working as a doffer at the Chronical Mill in nearby Belmont, and spent much of the 1920s and 1930s working at a succession of textile mills in and around Gastonia. But McCarn chafed under the regimentation and time-clock discipline of factory work, and, as a result, he spent much of his adult life searching for escape routes out of the circumscribed working-class life he faced in Gastonia’s textile mills. While still in his mid-teens, McCarn hoboed out west, eventually making it to Los Angeles, and his travels on the open road established a chronic pattern of extended rambling that would continue for much of the rest of his life.

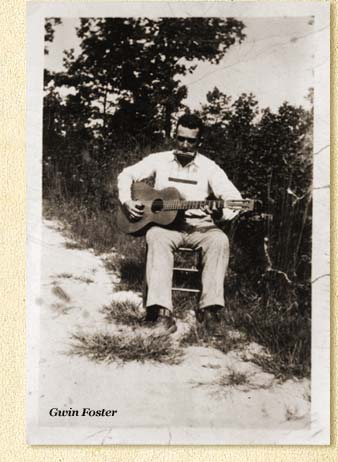

McCarn developed a serious interest in music relatively late in his life, although he had dabbled with the fiddle as a child. Beginning around 1926, at the age of twenty-one, he took up and soon mastered the harmonica, and then, using cheap, mass-produced instruction booklets, taught himself to play the guitar, eventually developing a raggy finger-picking style that he copied from an unidentified local guitarist he knew in Gastonia. One particularly important friendship that McCarn developed around this time was with Gwin Foster, who worked as a doffer with McCarn at the Victory Yarn Mills in South Gastonia. Apparently, Foster taught McCarn how to blow harmonica in a bluesy, ragtime style, and one can readily discern Foster’s strong influence on his protégé when listening to McCarn’s harmonica-and-guitar rag Gastonia Gallop.

Besides learning from Foster and other musicians he encountered in Gastonia, McCarn also developed his ragtime harmonica and guitar styles and musical repertoire by listening to the latest phonograph records, particularly those of Riley Puckett and Jimmie Rodgers. Around 1928, McCarn began writing his own songs, what he later called “little ditties,” based upon older traditional ballads and songs he learned from friends and neighbors, as well as the pieces he heard on current hillbilly records. Soon McCarn was performing some of his new compositions and playing back-up guitar with a group of six other millhands in a South Gastonia jug band called the Yellow Jackets. The seven-man band, which played both old-time songs and current pop hits, often entertained at house parties and dances in Gastonia’s working-class neighborhoods, and, occasionally, performed on Gastonia’s radio station, WRBU, which regularly broadcast evening concerts of local amateur singers and musicians.

McCarn’s interest in music might have remained merely that of an enthusiastic amateur had it not been for his chronic wanderlust. In May 1930, while rambling out west in search of work, McCarn stumbled into a recording career. By sheer coincidence, he arrived in Memphis, then an important regional center of African American blues and jug band music, at the same time that RCA-Victor was conducting a month-long field-recording session there at the Memphis Auditorium. Down to his last few dollars and hoping to pawn his prized Stewart guitar in order to get enough money to return home, McCarn learned of the recording session from two African American musicians. McCarn auditioned at the session, and so impressed Ralph S. Peer, Victor’s A & R man, that Peer invited him to record, on May 19, 1930, two original compositions. Everyday Dirt, a comic ballad about a faithless wife’s adultery and her angry husband’s retribution, is McCarn’s reworking of Will The Weaver, a traditional Anglo-American ballad about cuckoldry first published on English and Scottish broadsides as early as 1793. Cotton Mill Colic, which McCarn wrote around 1929, is a darkly comical complaint song about the starvation wages and poverty that plagued Carolina Piedmont textile workers, modeled, speculates old-time music historian Mark Wilson, on Bob Miller and Emma Dermer’s famous 1928 agricultural lament, Eleven Cent Cotton, Forty Cent Meat. For his studio work, McCarn received a one-time, flat fee payment of $25 per side, a windfall that enabled him to return to North Carolina.

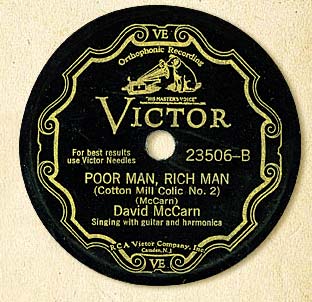

When McCarn’s record was released three months later in Victor’s “Old Familiar Tunes and Novelties” series, it sold briskly, especially in Gastonia and other Piedmont textile towns, despite the fact that, at seventy-five cents, a single Victor record cost millhands approximately one-third of a day’s wages. McCarn later claimed that one Gastonia music store, the S. W. Gardner Music Company on West Main Avenue, sold as many as a thousand copies. On the strength of McCarn’s debut record’s sales, Ralph Peer invited him to make ten more recordings for RCA-Victor over the course of the next year. On November 19, 1930, at a second Memphis session, McCarn waxed four sides on which he accompanied his singing with guitar and, with the aid of a rack, harmonica. Among these was a self-penned sequel to Cotton Mill Colic titled Poor Man, Rich Man (Cotton Mill Colic No. 2), on which McCarn recounts the exhausting drudgery of the work routine, as well as again complains, as he does on Cotton Mill Colic, about his low mill wages and inability to participate in the nation’s consumer culture beyond the barest minimum. Although McCarn is best remembered for his cotton mill songs, he also wrote and recorded several bawdy novelty numbers that captured his generation’s preoccupation with changing Jazz Age codes of behavior. Also at this session, McCarn recorded another original song, Take Them for a Ride, a risqué, thoroughly up-to-date treatment of the changing sexual mores introduced across the Carolina Piedmont by automobiles. Replete with details that indicate his familiarity with such intimate scenarios, McCarn’s “hot” guitar novelty number depicts women as assertive, independent figures who receive as much pleasure as men from booze, sex, and joy-riding. The next day, on November 20, McCarn recorded two harmonica-and-guitar ragtime instrumentals, one titled Gastonia Gallop, whose B part resembles Dill Pickle Rag, and the other, which went unissued, titled Mexican Rag. For these six recordings, McCarn received the standard fee of $25 per side, plus a small royalty, which, he recalled, amounted to about $50 a month for a while. When McCarn’s record was released three months later in Victor’s “Old Familiar Tunes and Novelties” series, it sold briskly, especially in Gastonia and other Piedmont textile towns, despite the fact that, at seventy-five cents, a single Victor record cost millhands approximately one-third of a day’s wages. McCarn later claimed that one Gastonia music store, the S. W. Gardner Music Company on West Main Avenue, sold as many as a thousand copies. On the strength of McCarn’s debut record’s sales, Ralph Peer invited him to make ten more recordings for RCA-Victor over the course of the next year. On November 19, 1930, at a second Memphis session, McCarn waxed four sides on which he accompanied his singing with guitar and, with the aid of a rack, harmonica. Among these was a self-penned sequel to Cotton Mill Colic titled Poor Man, Rich Man (Cotton Mill Colic No. 2), on which McCarn recounts the exhausting drudgery of the work routine, as well as again complains, as he does on Cotton Mill Colic, about his low mill wages and inability to participate in the nation’s consumer culture beyond the barest minimum. Although McCarn is best remembered for his cotton mill songs, he also wrote and recorded several bawdy novelty numbers that captured his generation’s preoccupation with changing Jazz Age codes of behavior. Also at this session, McCarn recorded another original song, Take Them for a Ride, a risqué, thoroughly up-to-date treatment of the changing sexual mores introduced across the Carolina Piedmont by automobiles. Replete with details that indicate his familiarity with such intimate scenarios, McCarn’s “hot” guitar novelty number depicts women as assertive, independent figures who receive as much pleasure as men from booze, sex, and joy-riding. The next day, on November 20, McCarn recorded two harmonica-and-guitar ragtime instrumentals, one titled Gastonia Gallop, whose B part resembles Dill Pickle Rag, and the other, which went unissued, titled Mexican Rag. For these six recordings, McCarn received the standard fee of $25 per side, plus a small royalty, which, he recalled, amounted to about $50 a month for a while.

Six months later, McCarn again recorded for RCA-Victor, this time at a field session in nearby Charlotte. Accompanying him at this session was another Gastonia millhand, his friend and sometime singing partner Howard Long (1905-1975), originally from near Canton, in Haywood County, in the mountains of western North Carolina. Around 1911, when he was still a child, the Long family settled in Gastonia, where his father and siblings found work in the mills. Howard himself began working at the Modena Cotton Mills at the age of fifteen. During the late 1920s, Long and McCarn both worked at the Winget Yarn Mill in South Gastonia and often performed together in the seven-man jug band called the Yellow Jackets. On May 19, 1931, in a downtown warehouse owned by RCA-Victor’s Charlotte distributor, McCarn and Long recorded four vocal duets, including Bay Rum Blues, a rollicking paean to the intoxicating properties of the title beverage, a popular hair tonic and aftershave lotion with a high alcohol content that became a popular liquor substitute in Carolina Piedmont towns during National Prohibition. “Now some use bay rum just for a tonic,” McCarn advises in one of the song’s most memorable lines, “But take it from me it’s best for your stomach.” At this Charlotte session, the duo also waxed a second sequel to Cotton Mill Colic titled Serves ’Em Fine. On Serves ’Em Fine, the swan song of his recording career, McCarn chronicles the 1920s economic collapse of the Piedmont textile industry and the cycle of poverty that ensnared mill worker families as the depression intensified. He also extends the blame for the blighted economic circumstances in which southern millhands found themselves, chiding workers for their own stupidity in leaving their mountain farms for Piedmont textile mills. On these sides, McCarn sang lead and played guitar and harmonica, while Long supplied vocal harmonies and, on Serves ’Em Fine, a lively, buzzing kazoo. These two recordings, released in July and August 1931, appeared under the billing “Dave and Howard.” But with the exception of his debut release, none of McCarn’s records apparently sold very well, and little more than a year after he first entered a makeshift Memphis studio, his promising recording career ended.

After his final recording session in 1931, McCarn reluctantly resumed working in Gaston County’s textile mills. He later served in the Army Signal Corps, where he learned the rudiments of electronics and radio repair, and opened a radio repair shop in Gastonia during World War II. Over the next decade he provided for himself and his new wife by combining radio repair and textile work. In 1950, McCarn quit his job at East Gastonia’s Rex Mill No. 1 and opened a television repair shop. During the 1930s, even after his recording career had ended, McCarn had continued to play music and to compose what he described as “humorous” songs, including such unrecorded titles as Mountain Gal and Peg’s Wooden Leg. But by the time record collectors and folklorists Archie Green and Ed Kahn interviewed him in Stanley, North Carolina, in 1961, he professed to have “lost interest” in music and had forgotten most of the words to Cotton Mill Colic and his other songs. He no longer even owned a guitar and had not played one regularly since 1959, when his last guitar had been ruined after a frozen water pipe burst in his repair shop. McCarn died on November 7, 1964, of aspirated pneumonia, resulting from cirrhosis of the liver, at the age of fifty-nine. His brief obituary in the Gastonia Gazette failed to mention his music and recording career, identifying him only as a “radio and TV repairman,” who had belonged to the Ebenezer Methodist Church and who had “lived in this community all of his life.” He was buried in Hillcrest Gardens Cemetery in Mount Holly, North Carolina, within five miles of his birthplace. Despite his small output of only a dozen commercial recordings, his songs, particularly Cotton Mill Colic, assured that his name would not be consigned to historical anonymity. McCarn is acclaimed today by music scholars and historians primarily for creatively translating his own working-class experiences and observations into songs of pointed commentary that resonated during the Great Depression with his embattled fellow millhands.

THREE ’BACCER TAGS

Another Gastonia act that recorded at RCA-Victor’s 1931 Charlotte field session was a twin-mandolin-and-guitar trio called the Three ’Baccer Tags, or, as they later became better known under the more dignified name, the Three Tobacco Tags, or, simply, the Tobacco Tags. During the Great Depression, their appealing repertoire of sentimental ballads, religious selections, pop songs, and comic novelty numbers, broadcast on stations in North Carolina and Virginia, made the Tobacco Tags one of the more popular radio hillbilly stringbands in upper Piedmont South. Originally, the Tobacco Tags consisted of mandolinists George Wade and Luther “Luke” Baucom and guitarist Reid Summey. All three men worked, at one time or another during the 1920s, in South Gastonia mills, and it was there that they first met and organized this stringband. Born in 1902 in McDowell County, in western North Carolina, Henry Luther Baucom (1902-1967), the group’s lead singer and mandolinist, had moved with his family to the textile town of Lowell, in Gaston County, before the age of eight. During the late 1920s, he worked, first as a twister hand and then as a section hand in the twister room, at the Seminole Mill in South Gastonia. There, around 1926, he met another Seminole employee, Edgar Reid Summey (1903-1975), a native Gaston Countian, the son of a textile mill superintendent. Baucom and Summey began teaming together to furnish the entertainment for church picnics, ice cream suppers, and other social gatherings in the mill communities Gaston County. Another local textile worker, mandolinist George Wade (ca. 1905-ca. 1958), originally from Davidson County, North Carolina, soon joined them to form a trio. Another Gastonia act that recorded at RCA-Victor’s 1931 Charlotte field session was a twin-mandolin-and-guitar trio called the Three ’Baccer Tags, or, as they later became better known under the more dignified name, the Three Tobacco Tags, or, simply, the Tobacco Tags. During the Great Depression, their appealing repertoire of sentimental ballads, religious selections, pop songs, and comic novelty numbers, broadcast on stations in North Carolina and Virginia, made the Tobacco Tags one of the more popular radio hillbilly stringbands in upper Piedmont South. Originally, the Tobacco Tags consisted of mandolinists George Wade and Luther “Luke” Baucom and guitarist Reid Summey. All three men worked, at one time or another during the 1920s, in South Gastonia mills, and it was there that they first met and organized this stringband. Born in 1902 in McDowell County, in western North Carolina, Henry Luther Baucom (1902-1967), the group’s lead singer and mandolinist, had moved with his family to the textile town of Lowell, in Gaston County, before the age of eight. During the late 1920s, he worked, first as a twister hand and then as a section hand in the twister room, at the Seminole Mill in South Gastonia. There, around 1926, he met another Seminole employee, Edgar Reid Summey (1903-1975), a native Gaston Countian, the son of a textile mill superintendent. Baucom and Summey began teaming together to furnish the entertainment for church picnics, ice cream suppers, and other social gatherings in the mill communities Gaston County. Another local textile worker, mandolinist George Wade (ca. 1905-ca. 1958), originally from Davidson County, North Carolina, soon joined them to form a trio.

Originally called the Jolly Rovers, the trio began broadcasting over WRBU in Gastonia, and in the spring of 1931, as a result of their radio performances, RCA-Victor officials recruited the band to record at a field session in Charlotte. On May 29, 1931, ten days after McCarn and Long, the band cut its first sides for Victor, under the direction of Ralph S. Peer. The first side the trio recorded at Charlotte, The Sharon School Teacher, went unissued, but the other two selections, mildly risqué numbers titled Get Your Head in Here and Ain’t Gonna Do It No More, featuring twin mandolins with guitar accompaniment, were coupled on Victor 23571. At this initial session, it was apparently Peer’s offhand remark, that if their records failed to sell they would be cast aside like “the tin tags on plugs of tobacco,” that provided the trio with the band name under which its two debut sides issued, the “Three ’Baccer Tags.”

Released during the depths of the Great Depression, the Three ’Baccer Tags’ record sold extremely poorly; the trio’s records from a second session, for Champion in August 1932, sold even fewer copies. Despite their initial miserable record sales, however, the band did go on to enjoy a great deal of commercial success. Beginning in 1934, the trio regularly broadcast over WPTF-Raleigh on a daily noontime radio show and over WBT-Charlotte on its popular Saturday-night Crazy Barn Dance, both of which were sponsored by the Carolinas and Georgia division of the Crazy Water Crystals Company, the manufacturers of a best-selling laxative. The Three Tobacco Tags’ growing radio popularity led to further recording sessions for RCA-Victor on its budget-priced Bluebird label. With an appealing mix of old sentimental songs, religious selections, current pop songs, and comic novelty numbers, the band’s later records sold quite well despite the ongoing Depression, and the group, which with several personnel changes eventually included as many as five members, recorded a total of eighty additional sides, many of which were written by Baucom and Summey, between 1936 and 1941. Meanwhile, George Wade left the group in 1938, but after his departure Baucom and Summey continued to perform together on the radio, tour professionally across the Southeast, and make commercial recordings, augmented at various time by other sidemen such as fiddlers Harold Hensley and Harvey Ellington, guitarist Bob Hartsell, and guitarist and bass player Sam Pridgin. In 1939, the Tobacco Tags moved to WRVA in Richmond, Virginia, and became regular cast members of its Old Dominion Barn Dance, where Baucom was known under the radio name “Looney Luke” and Summey became “Roly-Poly Reid.” By then, Baucom claimed that the band had performed in “more than 2,200 theatres, school auditoriums, churches and public halls” chiefly in Virginia and North Carolina, as well as in South Carolina, West Virginia, and Maryland. In 1942, the Tobacco Tags returned to WPTF in Raleigh for a three-year period. Meanwhile, during World War II, the Tobacco Tags played bills with Ernest Tubb, Pee Wee King, Mother Maybelle and the Carter Sisters, Minnie Pearl, and Grandpa Jones before disbanding in 1949.

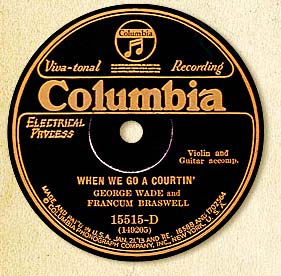

Prior to recording with the Three ’Baccer Tags, mandolinist George Wade had waxed a pair of vocal duets, at a 1929 Columbia field-recording session with a guitarist and harmonica player named Francum “Pickaloo” Braswell, a Caldwell County, North Carolina, farm laborer. James Francum Braswell (1908-1958) was born in 1908, the son of a farm family, in Piney, in Caldwell County, in western North Carolina. By 1920, however, his father and two siblings were working in cotton mill in nearby Lenoir, and although no definitive evidence has surfaced, Braswell himself may have worked in the mills, in either Caldwell or Gaston County. How Braswell and Wade met remains uncertain, nor is it clear how the duo came to audition for Columbia. However, in the fall of 1929, the pair traveled to Johnson City, Tennessee, to record at a field session, supervised by A & R man Frank B. Walker. There, on October 21, 1929, in a makeshift studio set up in a former cream separator station, Wade and Braswell waxed two vocal duets for Columbia’s “Familiar Tunes, Old and New” series: Think a Little, a rather secular admonition to uphold the biblical Golden Rule, and When We Go A Courtin’, a comical cautionary tale about the hazards of courting. Wade went on to record more than fifty sides with the Three Tobacco Tags (including another version of When We Go A Courtin’ at an October 1936 session in Charlotte) between 1931 and 1938, and an additional ten sides as the leader of George Wade and the Caro-Ginians, at a single session held in Rock Hill, South Carolina, in September 1938. But the two sides heard here represent the entire known recorded output of Braswell, who demonstrates himself to be a fine harmonica player with a style resembling that of Gwin Foster. Prior to recording with the Three ’Baccer Tags, mandolinist George Wade had waxed a pair of vocal duets, at a 1929 Columbia field-recording session with a guitarist and harmonica player named Francum “Pickaloo” Braswell, a Caldwell County, North Carolina, farm laborer. James Francum Braswell (1908-1958) was born in 1908, the son of a farm family, in Piney, in Caldwell County, in western North Carolina. By 1920, however, his father and two siblings were working in cotton mill in nearby Lenoir, and although no definitive evidence has surfaced, Braswell himself may have worked in the mills, in either Caldwell or Gaston County. How Braswell and Wade met remains uncertain, nor is it clear how the duo came to audition for Columbia. However, in the fall of 1929, the pair traveled to Johnson City, Tennessee, to record at a field session, supervised by A & R man Frank B. Walker. There, on October 21, 1929, in a makeshift studio set up in a former cream separator station, Wade and Braswell waxed two vocal duets for Columbia’s “Familiar Tunes, Old and New” series: Think a Little, a rather secular admonition to uphold the biblical Golden Rule, and When We Go A Courtin’, a comical cautionary tale about the hazards of courting. Wade went on to record more than fifty sides with the Three Tobacco Tags (including another version of When We Go A Courtin’ at an October 1936 session in Charlotte) between 1931 and 1938, and an additional ten sides as the leader of George Wade and the Caro-Ginians, at a single session held in Rock Hill, South Carolina, in September 1938. But the two sides heard here represent the entire known recorded output of Braswell, who demonstrates himself to be a fine harmonica player with a style resembling that of Gwin Foster.

FLETCHER AND FOSTER

One of the most influential musicians to emerge out of the local mill culture was Gwin Stanley Foster (1903-1954), a superb harmonica virtuoso and guitar player who worked for much of his adult life in textile mills in Dallas and Mount Holly. Foster’s father worked as a sawyer in a lumber mill in Caldwell County, North Carolina, where Gwin was born, in the community of Edgemont, on Christmas Day 1903. While he was still a child, his family moved, first to Clover, South Carolina, and then, shortly after 1910, to Dallas, North Carolina. There, his father found work as a section hand and entire family, including a teenaged Gwin, eventually took jobs in local cotton mills. One of the most influential musicians to emerge out of the local mill culture was Gwin Stanley Foster (1903-1954), a superb harmonica virtuoso and guitar player who worked for much of his adult life in textile mills in Dallas and Mount Holly. Foster’s father worked as a sawyer in a lumber mill in Caldwell County, North Carolina, where Gwin was born, in the community of Edgemont, on Christmas Day 1903. While he was still a child, his family moved, first to Clover, South Carolina, and then, shortly after 1910, to Dallas, North Carolina. There, his father found work as a section hand and entire family, including a teenaged Gwin, eventually took jobs in local cotton mills.

Foster had begun playing music while still a child, and eventually developed into a fine guitar picker and an even more superb harmonica player. In Gaston County, where he was known as “China” or “Chinee” because of his dark complexion, Foster’s extraordinary musical skills, particularly on his Hohner Marine Band harmonica, earned him a lustrous reputation. David McCarn, who knew him during the mid-1920s when the two worked together at the Victory Yarn Mills in South Gastonia, recalled that during slack periods and work breaks Foster often entertained his fellow employees with his harmonica wizardry. Foster, McCarn recalled, “was the best mouthharp player I’ve ever heard.” Foster’s powerful harmonica blowing “sounded like a pipe organ,” McCarn claimed, and, with its bent note trills, chirps, and warbles, was so ethereally beautiful that it could raise the hair on the back of one’s neck. Other informants recalled that Foster developed a show-stopping novelty piece that featured his playing the guitar and, with the aid of a rack around his neck, two harmonicas simultaneously. A February 19, 1927 item in the “Dallas Department” column of the Gastonia Daily Gazette lauded him as “a talented musician and expert on the harmonica and guitar, gifted naturally without a mite of instruction of any kind, a regular ace whose equal has not yet been found.”

In 1926, Foster met a drifting banjo-playing school teacher named Doctor Coble “Dock” Walsh, originally from the mountains of Wilkes County, North Carolina. The pair teamed up to play music at entertainments, both in Gaston and Wilkes Counties, and soon auditioned and secured a recording contract with the Victor Talking Machine Company. In 1927, at a February session in Atlanta and an August one in Charlotte, Foster and Walsh recorded a total of ten harmonica-guitar-and-banjo duets for the Victor label as the Carolina Tar Heels, a name bestowed upon the duo by A & R man Ralph S. Peer. The duo’s records, particularly Bring Me a Leaf from the Sea and I’m Going to Georgia, enjoyed strong commercial sales. But with Walsh’s home in Wilkes County and Foster’s in Gaston County, the duo lived too far apart to practice and perform together regularly. Nor did Walsh, who favored more traditional, old-timey material, share Foster’s preference for contemporary Tin Pan Alley songs. As a result of divergent musical tastes and the considerable distance separating their homes, the duo broke up, but Ralph Peer did manage to reunite them, under the billing of the “Original Carolina Tar Heels,” for one final session in Atlanta in February 1932 that yielded four additional sides.

Meanwhile, around 1927, Foster found a new musical partner who lived nearby, a Mount Holly singer, yodeler, and guitarist named David O. Fletcher (1900-1958), who was originally from Chowan County, North Carolina. During the mid-1920s, Fletcher worked as a comber in Gaston County textile mills, first in Belmont and then in Mount Holly, where he played the bass violin in the Men’s Bible Class Orchestra at the Mount Holly Methodist Church. In 1927, while living in Mount Holly, Fletcher won the $5.00 first prize on guitar at the Old Fiddlers’ Convention in Lowell. Soon, Fletcher and Foster were furnishing the music at parties, dances, and even civic club meetings. For a time in 1928, the duo, dubbed the Carolina Twins, had a regular half-hour Tuesday night program on WBT in Charlotte. On occasion, Fletcher and Foster also played in a larger stringband that featured a repertoire consisted chiefly of contemporary Jazz Age pop hits such as Lazy River, Five Foot Two, Eyes of Blue, and I’m Looking over a Four Leaf Clover. Both Fletcher and Foster shared a fondness for such music, and at their first recording session, in February 1928 in Atlanta, the duo had actually prepared arrangements for several current popular songs and planned to record them. But, as old-time music historian Tony Russell explains, Victor producer Ralph Peer showed no interest in self-taught singers and musicians recording yet another version of songs like Wang Wang Blues or Wabash Blues, and instead encouraged the duo to concentrate on old-time selections better suited to the label’s hillbilly catalog.

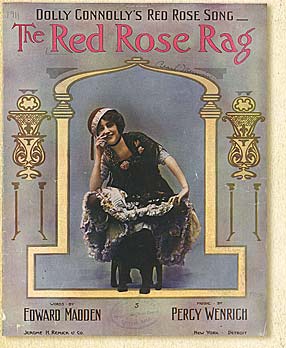

Between 1928 and 1930, Fletcher and Foster recorded a total of twenty-one sides, all but two of which appeared under the artist credit of the “Carolina Twins.” All of the duo’s selections featured on this anthology stemmed from a two-day Victor recording session in Atlanta in late November 1929. On November 28, 1929, the duo recorded six twin guitar-and harmonica sides, including Gal of Mine Took My Licker from Me, a drunkard’s lament; Southern Jack, a railroad song commonly found in African American tradition; I Want My Black Baby Back, a version of the 1898 “coon song,” All I Wants Is My Black Baby Back, written by Tom Daly and Gus Edwards; and A Change in Business All Around, a song of Jazz Age social commentary, versions of which several other hillbilly acts, including Roy Harvey, Wade Mainer and Zeke Morris, and Claude Casey, later recorded during the 1930s. The next day, on November 29, Fletcher and Foster returned to the studio to cut two “hot” ragtime guitar duets: Charlotte Hot Step, a locally titled tune of unknown origin that features Foster’s distinctive harmonica trills and warbles; and Red Rose Rag, a rendition of Percy Wenrich’s 1911 ragtime tune of that name. All of these sides were released in Victor’s old-time record series, then called “Native American Melodies,” but, unlike all of the Carolina Twins’s other records, the two guitar instrumentals were issued under the artist credit of “Fletcher & Foster,” perhaps, as Tony Russell has speculated, “to distance them from the rather different repertoire that by now was associated with the Carolina Twins brand.” Between 1928 and 1930, Fletcher and Foster recorded a total of twenty-one sides, all but two of which appeared under the artist credit of the “Carolina Twins.” All of the duo’s selections featured on this anthology stemmed from a two-day Victor recording session in Atlanta in late November 1929. On November 28, 1929, the duo recorded six twin guitar-and harmonica sides, including Gal of Mine Took My Licker from Me, a drunkard’s lament; Southern Jack, a railroad song commonly found in African American tradition; I Want My Black Baby Back, a version of the 1898 “coon song,” All I Wants Is My Black Baby Back, written by Tom Daly and Gus Edwards; and A Change in Business All Around, a song of Jazz Age social commentary, versions of which several other hillbilly acts, including Roy Harvey, Wade Mainer and Zeke Morris, and Claude Casey, later recorded during the 1930s. The next day, on November 29, Fletcher and Foster returned to the studio to cut two “hot” ragtime guitar duets: Charlotte Hot Step, a locally titled tune of unknown origin that features Foster’s distinctive harmonica trills and warbles; and Red Rose Rag, a rendition of Percy Wenrich’s 1911 ragtime tune of that name. All of these sides were released in Victor’s old-time record series, then called “Native American Melodies,” but, unlike all of the Carolina Twins’s other records, the two guitar instrumentals were issued under the artist credit of “Fletcher & Foster,” perhaps, as Tony Russell has speculated, “to distance them from the rather different repertoire that by now was associated with the Carolina Twins brand.”

The Carolina Twins recorded a final session for Gennett in Richmond, Indiana, in September 1930. Although Fletcher, then living in Mecklenburg County, identified his occupation in the 1930 census as “Artist, Talking Mach. Rec.,” this session for Gennett marked the end of his commercial recording career. Fletcher eventually left the Gaston-Mecklenburg counties area, moving, first, to Richmond, Indiana, and, then, to Mansfield, Ohio, before returning to Mount Holly in the early 1950s. There, he worked as a security guard. Dave Fletcher died in 1958 at the North Carolina Cancer Institute in Lumberton.

Gwin Foster, meanwhile, went on to make additional recordings, some fifty sides in all, including duets with Clarence “Tom” Ashley (Ashley and Foster), with Dock Walsh (the Original Carolina Tar Heels), and stringband numbers with the Blue Ridge Mountain Entertainers between 1931 and 1933. During the mid-to-late 1930s, according to Shannon Grayson, a later member of the Tobacco Tags, Foster played with several hillbilly radio bands, including the Tobacco Tags on WRVA in Richmond, Virginia. Foster cut his last two sides, for Victor’s Bluebird label, in Rock Hill, South Carolina, in February 1939, with uncredited accompaniment provided by the Tobacco Tags.

Foster never made music a full-time pursuit, and he spent much of his adult life working in the textile mills of Mount Holly and Dallas. Like David McCarn, Foster appears, sadly, to have been a victim of his own self-destructive drinking and antisocial tendencies, another tremendous talent curtailed by alcoholism. He died of a heart attack in his home in Dallas on Thanksgiving Day, 1954, at the age of fifty. Today, Gwin Foster is widely considered one of the greatest harmonica players on prewar hillbilly records, and his old 78 rpm recordings, particularly those of the Carolina Tar Heels and the Carolina Twins, are highly prized by record collectors.

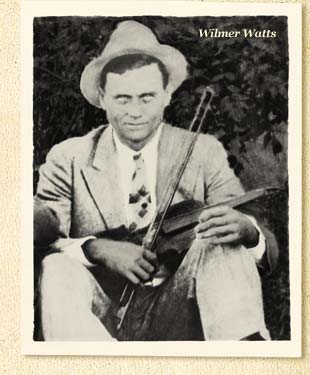

WILMER WATTS

Another well-known musician employed in Gaston County cotton mills was singer and banjo player Wilmer Wesley Watts (1897-1943), who worked as a loom fixer at the Climax Spinning Company in Belmont and performed with several local stringbands during the mid-to-late 1920s. Born in 1897, Watts was originally from Mount Tabor (now Tabor City), a market town in Columbus County, in the southeastern corner of North Carolina. He developed a serious interest in music as a child, and, although he never learned to read music, he did play several stringed instruments, including the fiddle, banjo, guitar, steel guitar, and autoharp, as well as the harmonica, drum, and even the musical saw. He became so musically proficient, in fact, that he sometimes performed as a one-man band, playing five instruments at once. Around 1931, according to family members, Watts won first prize with his act in a contest at a Mount Holly theater. Uncle Dave Macon reportedly served as one of the contest judges. Watts was an avid fan of hillbilly music, and owned a cylinder talking machine and later a disc phonograph on which he enjoyed listening to the latest records of Gid Tanner and the Skillet Lickers, Jimmie Rodgers, Jimmie Davis, and his favorite, Roy Acuff. Another well-known musician employed in Gaston County cotton mills was singer and banjo player Wilmer Wesley Watts (1897-1943), who worked as a loom fixer at the Climax Spinning Company in Belmont and performed with several local stringbands during the mid-to-late 1920s. Born in 1897, Watts was originally from Mount Tabor (now Tabor City), a market town in Columbus County, in the southeastern corner of North Carolina. He developed a serious interest in music as a child, and, although he never learned to read music, he did play several stringed instruments, including the fiddle, banjo, guitar, steel guitar, and autoharp, as well as the harmonica, drum, and even the musical saw. He became so musically proficient, in fact, that he sometimes performed as a one-man band, playing five instruments at once. Around 1931, according to family members, Watts won first prize with his act in a contest at a Mount Holly theater. Uncle Dave Macon reportedly served as one of the contest judges. Watts was an avid fan of hillbilly music, and owned a cylinder talking machine and later a disc phonograph on which he enjoyed listening to the latest records of Gid Tanner and the Skillet Lickers, Jimmie Rodgers, Jimmie Davis, and his favorite, Roy Acuff.

Around 1921, after settling in Belmont, Watts immersed himself in the local music scene, and by 1926, he and a steel guitarist and singer named Frank Wilson, with whom he worked at the Climax Mill, were teaming up to entertain their fellow millhands at Gaston County social gatherings. Research by Bob Carlin reveals that Wilson was born in Chinquapin, in Rockingham County, North Carolina, and that his full name was Percy Alphonso “Frank” Wilson (1900-?). Like Wilmer Watts, Wilson was a talented multi-instrumentalist. As a child, he took music lessons and learned to read musical notation, and, later as an adult, he sometimes taught piano, violin, and guitar out of his home. Although trained as a barber, he spent much of his early adulthood working in textile mills in Alamance County, North Carolina, before settling in Belmont, where he met Wilmer Watts, with whom he made eight duets for Paramount in 1927 under the name “Watts and Wilson.” How Watts and Wilson came to record has been lost to history, but in the winter of 1927, the duo traveled to Chicago, where they made their first recording, a vocal duet of The Sporting Cowboy, accompanied by banjo and guitar, in either January or February 1927 for Paramount. This single side went unissued, but the duo must have impressed Paramount officials. Some two to three months later, in April 1927, Watts and Wilson returned to Paramount’s recording studios in Chicago, this time accompanied by another Belmont millhand, singer and guitarist Charles H. Freshour (1900-1959), who also worked at the Climax Mill. Born in 1900 in the city of Newport, in the mountains of western Tennessee, Freshour learned to play guitar around the age of nine, according to his family, from a local black street singer. Like Watts, Freshour was adept on a number of stringed instruments, but preferred the guitar, and according to his family, he also wrote several songs, including The Aderholt Murder, Bonnie Bess, The Fate of Rhoda Sweetin, and Walk Right in Belmont.

At their April 1927 session in Chicago, Watts and Wilson, accompanied by Freshour on guitar, waxed seven selections, one of which, Walk Right in Belmont, is a reworking of Midnight Special, an extensively recorded prison song from African American tradition that Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter popularized in the 1940s. Freshour, who reportedly wrote Walk Right in Belmont, probably sings lead on this recording. Paramount released Walk Right in Belmont in its new “Old Time Tunes” series, credited only to “Watts and Wilson,” and on the auxiliary Broadway label, under the artist pseudonym of “Weaver and Wiggins.” Shortly after this session, Frank Wilson moved to Burlington, North Carolina, 120 miles to the northeast. Between 1928 and 1929, he went on to tour and record more than twenty sides with several other hillbilly stringbands, including the acclaimed vaudeville troupes H. M. Barnes and His Blue Ridge Ramblers and the Hill Billies/Al Hopkins and His Buckle Busters. And although he made his first recordings with a Gaston County stringband, Wilson is best remembered today for his association with the Charlie Bowman-Roe Brothers musical circle, based in East Tennessee and southwest Virginia, whose members performed at various times with both of these vaudeville stringbands.

After Wilson left the area around 1927, Watts organized a stringband trio called the Gastonia Serenaders, with Freshour and another Belmont textile worker, steel guitarist Palmer Rhyne, whom he had met while playing at a local dance. Harvey Palmer Rhyne (1904-1967) was born in Gaston County in 1904, probably in McAdenville, where his father worked as a weaver at one of the town’s three McAden Mills. In late October 1929, the band, now renamed Wilmer Watts and the Lonely Eagles (apparently a reference to aviator Charles Lindbergh’s famous nickname), waxed sixteen sides during a marathon two-day session for Paramount in New York City. Been on the Job Too Long is a garbled version of the African American murder ballad better known as Duncan and Brady, which was based upon an actual event, the 1880 shooting death of an Irish policeman by a black bartender in St. Louis, Missouri. Bonnie Bess, a sentimental ballad about a railroad engineer’s daughter, is based upon an anonymous poem, “The Night Express,” which appeared in the November 1893 issue of the Locomotive Engineers’ Monthly Journal. Charles Freshour, whose family claimed he wrote the song, probably set the poem to music. In April 1927, Watts and Wilson had recorded an earlier version of this song as The Night Express, and its retitling probably represents Watts and the Lonely Eagles’ efforts to skirt the fact that Paramount already had this prior recording of the song in its hillbilly catalog. She’s A Hard Boiled Rose, a song about a tough, gold-digging “dame,” derives from the 1924 Tin Pan Alley number, Hard Boiled Rose, written by Al Dubin, Jimmie McHugh, and Irwin Dash, and perhaps best remembered as the theme song for stripper Gypsy Lee Rose. At this session, Wilmer Watts and the Lonely Eagles also waxed two traditional ballads: Sleepy Desert, a tale of star-crossed lovers, better known as The Drowsy Sleeper, and found on other prewar hillbilly records under the more common titles Oh Molly Dear and Katie Dear; and Working for My Sally, another narrative song, this one about unrequited love, more commonly known as Joe Bowers. Like David McCarn, Watts and his stringband also recorded an occupational song, Cotton Mill Blues, based on George D. Stutts’s poem “A Factory Rhyme,” originally published in his chapbook, Picked Up Here and There (1900). As with The Night Express/Bonnie Bess, Freshour was probably the one responsible for transforming this textile mill poem by Stutts, who worked at Crown Mills in Greensboro, North Carolina, into a song. On this record, Watts and the band confront the social stigma attached to Carolina Piedmont mill workers, complaining that “uptown people” call them “trash” and the “ignorant factory set.” Although Watts played at least eight instruments and in the only known photograph of him he is holding a fiddle, he apparently played only the banjo on his commercially released sides. He is commonly assumed to have sung lead on all of the Lonely Eagles sides, but a comparison of these records reveals that at least two different singers, probably Watts and Freshour, handled the lead vocals. Released during the depths of the Great Depression, on a label that lacked a national distribution network, Wilmer Watts and the Lonely Eagles’ records sold poorly, and today are exceedingly rare, with only one or two copies of some of them known to exist. On them nonetheless can be found what old-time music historian Norm Cohen calls “several outstanding musical gems.” After Wilson left the area around 1927, Watts organized a stringband trio called the Gastonia Serenaders, with Freshour and another Belmont textile worker, steel guitarist Palmer Rhyne, whom he had met while playing at a local dance. Harvey Palmer Rhyne (1904-1967) was born in Gaston County in 1904, probably in McAdenville, where his father worked as a weaver at one of the town’s three McAden Mills. In late October 1929, the band, now renamed Wilmer Watts and the Lonely Eagles (apparently a reference to aviator Charles Lindbergh’s famous nickname), waxed sixteen sides during a marathon two-day session for Paramount in New York City. Been on the Job Too Long is a garbled version of the African American murder ballad better known as Duncan and Brady, which was based upon an actual event, the 1880 shooting death of an Irish policeman by a black bartender in St. Louis, Missouri. Bonnie Bess, a sentimental ballad about a railroad engineer’s daughter, is based upon an anonymous poem, “The Night Express,” which appeared in the November 1893 issue of the Locomotive Engineers’ Monthly Journal. Charles Freshour, whose family claimed he wrote the song, probably set the poem to music. In April 1927, Watts and Wilson had recorded an earlier version of this song as The Night Express, and its retitling probably represents Watts and the Lonely Eagles’ efforts to skirt the fact that Paramount already had this prior recording of the song in its hillbilly catalog. She’s A Hard Boiled Rose, a song about a tough, gold-digging “dame,” derives from the 1924 Tin Pan Alley number, Hard Boiled Rose, written by Al Dubin, Jimmie McHugh, and Irwin Dash, and perhaps best remembered as the theme song for stripper Gypsy Lee Rose. At this session, Wilmer Watts and the Lonely Eagles also waxed two traditional ballads: Sleepy Desert, a tale of star-crossed lovers, better known as The Drowsy Sleeper, and found on other prewar hillbilly records under the more common titles Oh Molly Dear and Katie Dear; and Working for My Sally, another narrative song, this one about unrequited love, more commonly known as Joe Bowers. Like David McCarn, Watts and his stringband also recorded an occupational song, Cotton Mill Blues, based on George D. Stutts’s poem “A Factory Rhyme,” originally published in his chapbook, Picked Up Here and There (1900). As with The Night Express/Bonnie Bess, Freshour was probably the one responsible for transforming this textile mill poem by Stutts, who worked at Crown Mills in Greensboro, North Carolina, into a song. On this record, Watts and the band confront the social stigma attached to Carolina Piedmont mill workers, complaining that “uptown people” call them “trash” and the “ignorant factory set.” Although Watts played at least eight instruments and in the only known photograph of him he is holding a fiddle, he apparently played only the banjo on his commercially released sides. He is commonly assumed to have sung lead on all of the Lonely Eagles sides, but a comparison of these records reveals that at least two different singers, probably Watts and Freshour, handled the lead vocals. Released during the depths of the Great Depression, on a label that lacked a national distribution network, Wilmer Watts and the Lonely Eagles’ records sold poorly, and today are exceedingly rare, with only one or two copies of some of them known to exist. On them nonetheless can be found what old-time music historian Norm Cohen calls “several outstanding musical gems.”

Shortly after his recorded career ended in 1929, Watts and his family moved to Horry County, South Carolina, where he earned a living as a tenant farmer for a time. Throughout much of the rest of the 1930s, Watts continued working as a loom fixer in the mills in Belmont and Bessemer City, and, fifty miles to the northwest, in Hickory through the Great Depression. Watts also continued to play music, including occasionally as a one-man band. During the mid-1930s, while living in Bessemer City and working at the Bessemer Cotton Mill, Watts organized the Watts Gospel Singers with his oldest daughters. The group performed in churches, at revivals, and even on street corners, and for a couple of years in the late 1930s, even performed on two regular radio shows, with an early morning program at 5:30 A.M. on WSPA in Spartanburg, South Carolina, and an evening program at 5:00 P.M. on WBT in Charlotte, North Carolina. Around 1939, however, Watts was diagnosed with stomach cancer, and his illness forced him to retire from mill work and music making. He and his family moved to St. Pauls, in Robeson County, North Carolina, where he operated a gas station until his death in 1943 at the age of forty-seven. Following their father's death in 1943, Watts’s daughters, eventually joined by one of their husbands, continued performing as the Watts Gospel Singers and later as the Watts Gospel Quartet into at least the 1960s.

|