David McCarn’s Cotton Mill Colic

by Patrick Huber

Patrick Huber is the author of Linthead Stomp, The Creation of Country Music in the Piedmont South Patrick Huber is the author of Linthead Stomp, The Creation of Country Music in the Piedmont South

Listen to Cotton Mill Colic in Windows Media format

Listen to Cotton Mill Colic in QuickTime format

With its biting satire and dark comedy, David McCarn’s Cotton Mill Colic expresses a deep sense of working-class anger and resentment seldom heard on commercially recorded hillbilly records of the 1920s and 1930s. Unlike almost all of the other dozen or so textile songs that appeared on record before 1942, however, Cotton Mill Colic is not specifically about the miseries of factory labor. Instead, the song concerns itself with working-class consumption –or rather, the lack of it –and the vicious downward cycle of debt and poverty that ensnared tens of thousands of textile worker families. In Cotton Mill Colic, written around 1929, McCarn complains about the refusal of mill managers to pay a living wage with which he can purchase not only those small luxuries he desires, but also the barest of life’s necessities. The paltry wages millhands received, McCarn asserts, emasculate workingmen by preventing them from fulfilling their traditional male roles as family breadwinners.

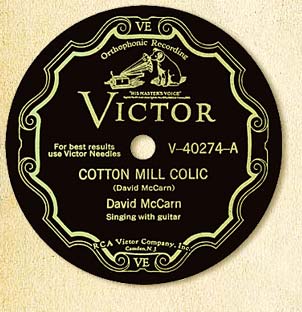

When he recorded Cotton Mill Colic at a May 1930 field-recording session in Memphis, Tennessee, McCarn probably never intended to make a serious social statement. He was, as the song’s title indicates, “colicking,” or merely grousing. Nonetheless, the song struck a chord with hard-hit millhands in the midst of massive layoffs and stepped-up work rhythms in the Piedmont South’s ailing textile industry. McCarn’s song fostered, even as it was inspired by, the stirrings of class consciousness that exploded between 1929 and 1931 in one of the largest waves of textile strikes to ever engulf the Piedmont South. More so than any other textile song found on prewar hillbilly discs, Cotton Mill Colic spread rapidly across the Depression-era South through the powerful medium of phonograph records. And more so than these other textile songs, Cotton Mill Colic circulated orally within southern working-class communities during the Great Depression and eventually emerged as a classic protest song in folk revival circles and trade unionist groups during the 1950s and 1960s.

In September 1930, only a month after its release, McCarn’s recording of Cotton Mill Colic sparked a controversy during the strike at the Riverside and Dan River Cotton Mills Company in Danville, Virginia. Doug DeNatale and Glenn Hinson’s research not only reveals how the song circulated among strikers during that protracted labor struggle, but also illuminates the conflicting political connotations that both textile manufacturers and employees ascribed to McCarn’s song. “Seeing the commercial possibilities of the song during the strike,” they write, “Luther B. Clarke, a Danville record store owner who had previously arranged recording sessions for several mill worker musicians, promoted the record through his store and arranged to have it played on a local radio station... In response, H. R. Fitzgerald, the president of Dan River Mills, pressured the local media to suppress the song on the grounds that ‘it was degrading to cotton mill work,’” and in deference to Fitzgerald, one of the local radio stations, probably WBTM, stopped broadcasting McCarn’s record.

By then, however, Cotton Mill Colic had already become wildly popularity among Danville strikers. Tom Tippett, a labor organizer and activist from Brookwood Labor College in Katonah, New York, heard Cotton Mill Colic at a mid-January 1931 United Textile Workers union rally in Danville, in a house rented from the Ku Klux Klan. “A small boy, not yet in his teens, sang a solo accompanying himself with a guitar swung from his shoulder,” Tippett wrote in When Southern Labor Stirs (1931). “It was called Cotton Mill Colic and accurately portrayed in a comic vein the economics of the textile industry, as well as the tragedy of cotton mill folk. . . .”

Although Cotton Mill Colic figured prominently in the Danville strike, some musicians embraced Cotton Mill Colic primarily for its satirical humor. In the mid-1930s, Bill Bolick learned a version of McCarn’s song from a friend in his hometown of Hickory, North Carolina. Bolick, a mandolin player, and his guitarist brother Earl, who performed together on radio and records between 1935 and 1951 as the Blue Sky Boys, reprised McCarn’s song on their 1965 comeback album, Presenting The Blue Sky Boys. Both of the Bolicks’s parents worked in Hickory textile mills, but unlike the Danville strikers who incorporated the song into their union meetings, Bill Bolick did not invest it with any overtly political meanings. “I didn’t sing Cotton Mill Colic with the idea of protesting,” he explained. “I thought it was more of a comedy song.”

Not only was McCarn’s Cotton Mill Colic enormously popular in Piedmont textile towns during the Great Depression, but it also penetrated Southern Appalachian communities. In 1938, Joe Sharp, a mandolinist and guitarist from the New Deal resettlement community of Skyline Farms, Alabama, traveled to Washington, D.C. that May as one of the members of the Skyline Farms band and dance team to entertain First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and her guests at a White House garden party. While in the nation’s capital, Sharp recorded the song for Alan Lomax, the director of the Library of Congress’ Archive of American Folk-Song in Washington, D.C. Consequently, Cotton Mill Colic entered the American folksong canon, and has been included in such now-classic American folksong anthologies as John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax’s Our Singing Country: A Second Volume of American Ballads and Folk Songs (1941) and in Alan Lomax’s The Folk Songs of North America (1960), in which he called Cotton Mill Colic “the best of all . . . cotton-mill songs.” It has also appeared in Hard Hitting Songs for Hard-Hit People (1967), which Lomax compiled and edited in collaboration with folksingers Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger. In his introduction to the song in that volume, Guthrie identified Cotton Mill Colic as “one of my favorite songs.” “You can tell by the way its wrote up,” he noted, “that it aint ‘put on’—I mean its the real thing.” As a result of its inclusion in such prominent folksong anthologies, Cotton Mill Colic emerged as an emblematic protest song within the American folksong revival and the labor movement during the 1950s and 1960s. It has been extensively recorded on post-World War II albums by other artists, the first of whom, Pete Seeger, cut a version of the song on his 1956 Folkways concept LP, American Industrial Ballads. More than ten other artists, including J. E. Mainer, Mike Seeger, Roy Berkeley, and Joe Glazer, have also covered Cotton Mill Colic.

In 1973, the West German company Folk Variety Records reissued all of McCarn’s extant commercial recordings on an album titled Singers of the Piedmont, and brought his music to the attention of a new generation of scholars and fans. Since then, McCarn’s recording of Cotton Mill Colic has been reissued on no fewer than seven historical reissue CDs, but its appearance on Gastonia Gallop represents the first release of Cotton Mill Colic along with its two sequels on a single CD anthology. Cotton Mill Colic secured McCarn’s legacy within the history of hillbilly music, and largely as a result of the song’s widespread popularity after World War II, McCarn is, as one of his biographers, Charles K. Wolfe, has noted, probably better known today, almost eighty years after his hillbilly records were originally released, than he was during his brief recording career.

|